Tia Blassingame Artist, Professor and Press Director Scripps College

Johanna Drucker Moderator, Artist, Breslauer Professor, Information Studies, UCLA

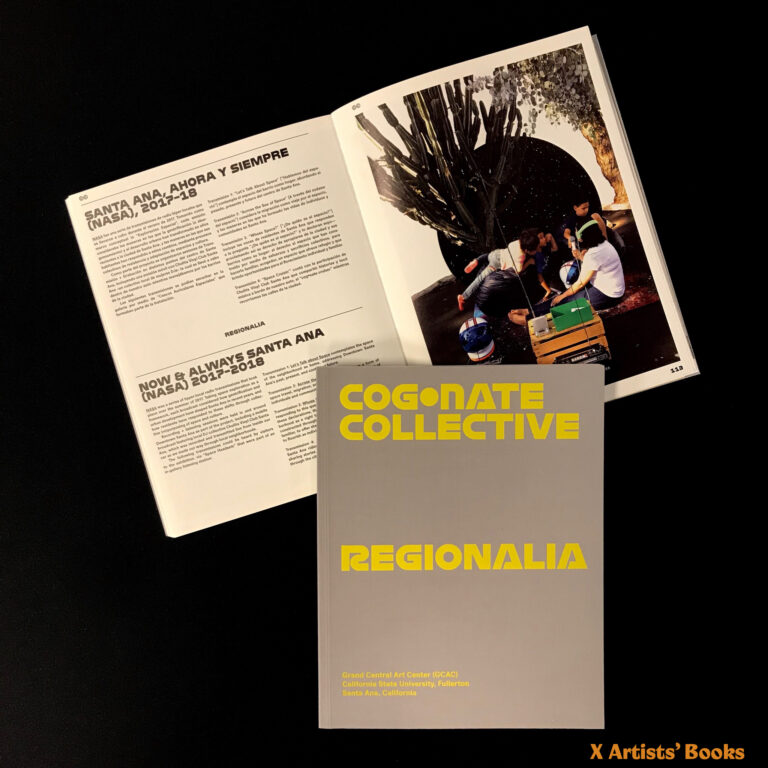

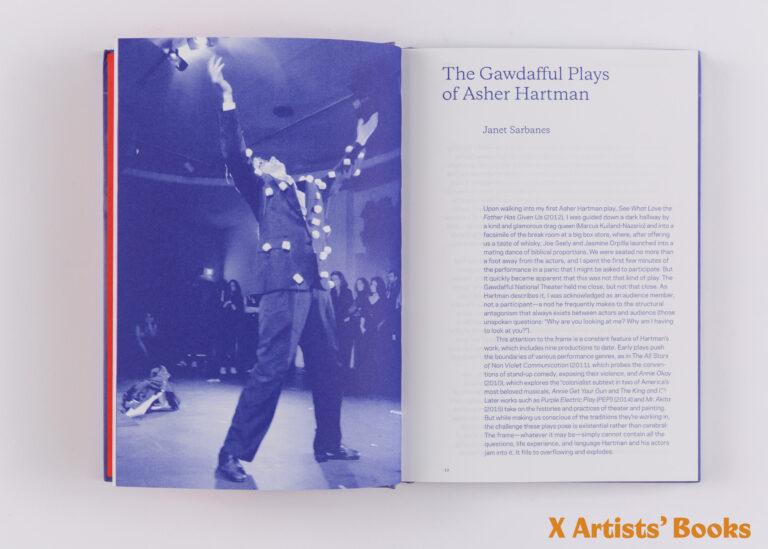

Alexandra Grant Artist, Publisher X Artists’ Books

Marcia Reed Chief Curator, The Getty Research Institute

Susan Sironi Artist

Why books NOW? Are books symbolic objects? Have books created political change? What is it that makes artists’ book a unique /compelling art form? Can artists’ books advance social justice for women? This panel discussion will tackle the history and current state of independent press and self-publishing by women artists making books as an art form.

This panel discussion focuses on book aesthetics in the history and current state of independent press and self-publishing by women artists. Though increasingly active in California publishing over the last century, as in so many areas, women have not always been as visible as their contributions deserve. Showcasing a diverse range of women artists and curators, the panel address the ways in which women artists’ publications create a distinct discourse, whether that arises from editorial ethics or curatorial decisions, feminist methods, specific topics and themes, or anticipated audiences. Most importantly, the panel will call attention to vibrant works of art being made in the book format designed to bring transformative points of view into published form.

This event is co sponsored with: Now Be Here Guest Curator Initiative, Scripps College, UCLA Center for the Study of Women, & X Artists’ Books

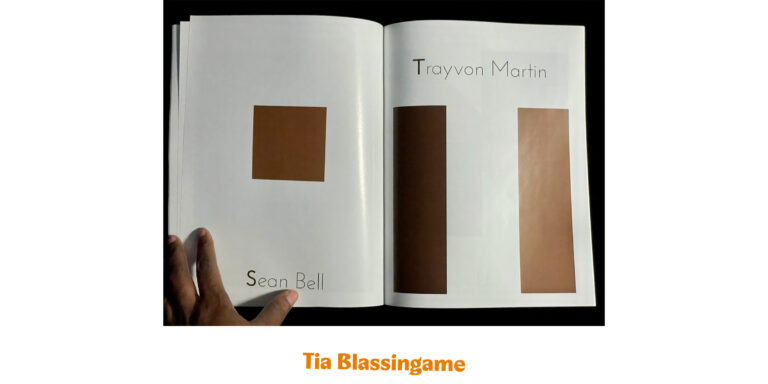

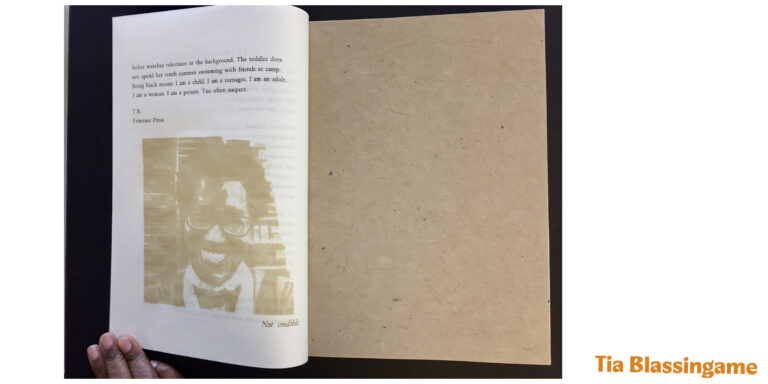

Tia Blassingame

A book artist and printmaker exploring the intersection of race, history, and perception, Tia Blassingame often incorporates archival research and her own poetry in her artist’s book projects for nuanced discussions of racism in the United States. In 2019, Blassingame founded the Book/Print Artist/Scholar of Color collective to bring Book History and Print Culture scholars into conversation and collaboration with Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) book artists, papermakers, curators, letterpress printers, printmakers for building community and support systems. Blassingame is an Assistant Professor of Book Arts at Scripps College and serves as the Director of Scripps College Press.

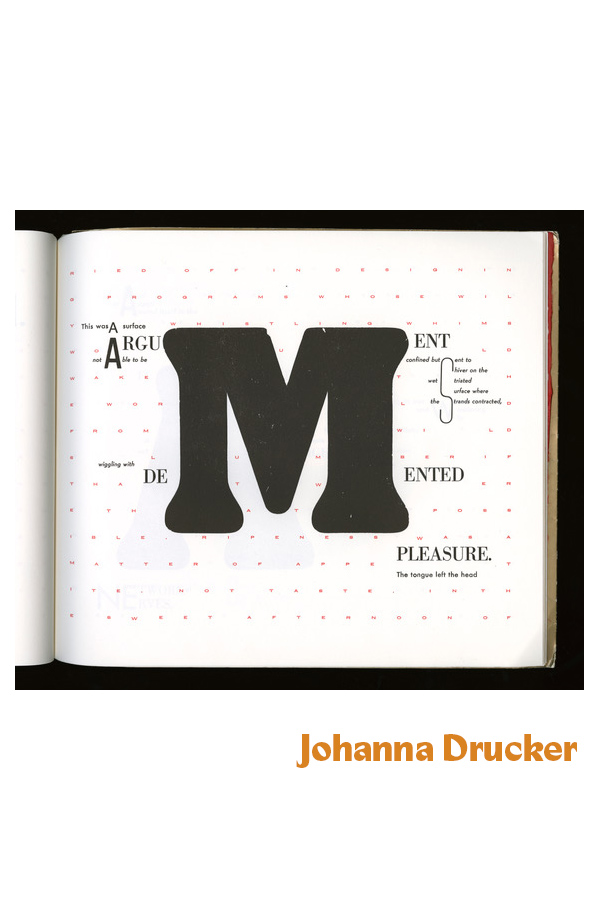

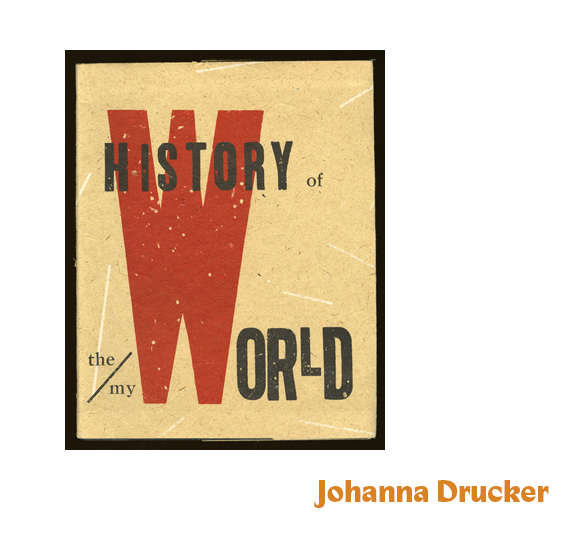

Johanna Drucker

Johanna Drucker is Distinguished Professor and Breslauer Professor in the Department of Information Studies at UCLA. She is internationally known for her work in the history of graphic design, typography, experimental poetry, fine art, and digital humanities. Drucker’s artist‘s books were the subject of a travelling retrospective, Druckworks: 40 years of books and projects, in 2012-2014. Her new titles include Visualization and Interpretation (MIT Press, 2020), and Iliazd: Meta-Biography of a Modernist (Johns Hopkins University Press 2020), and Digital Humanities: An introduction to Digital Methods (Routledge, 2021).

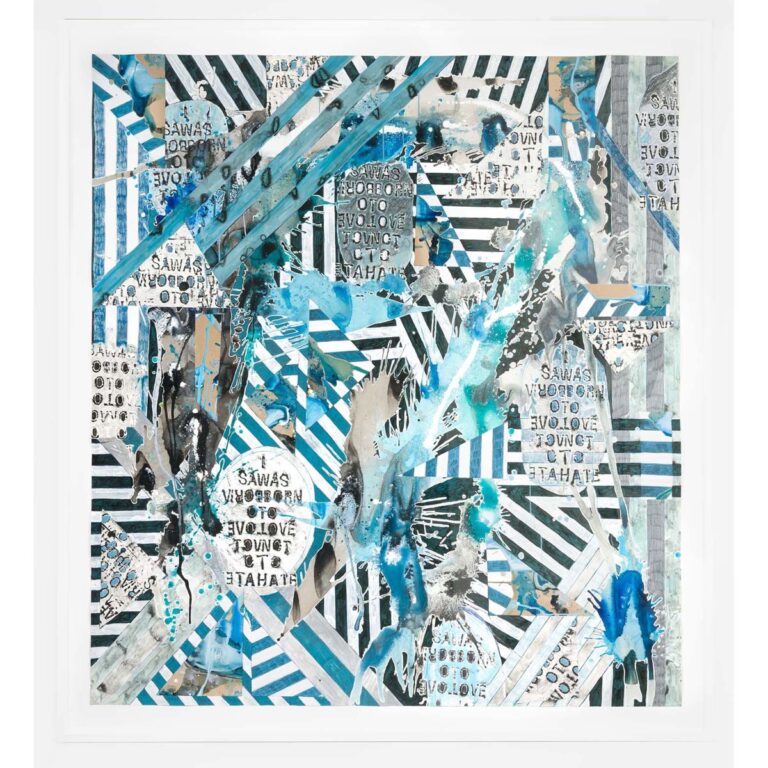

Alexandra Grant

Alexandra Grant is a Los Angeles-based visual artist who examines language and written texts through painting, drawing, sculpture, video, and other media. Her work has also been exhibited at the Orange County Museum of Art, CA, Contemporary Museum, Baltimore, MD, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA), and the Pasadena Museum of California Art, among others. She has received the COLA Individual Artist Fellowship and a grant from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation. She is the creator of the grantLOVE project, which raises funds for arts-based non-profits such as Heart of Los Angeles (HOLA), Project Angel Food, Art of Elysium, 18th Street Arts Center, and LAXART. In 2017, Grant co-founded X Artists’ Books (a publishing house for artist-centered book) and has published 8 literary works of art to date and will be releasing 6 new publications in 2021.

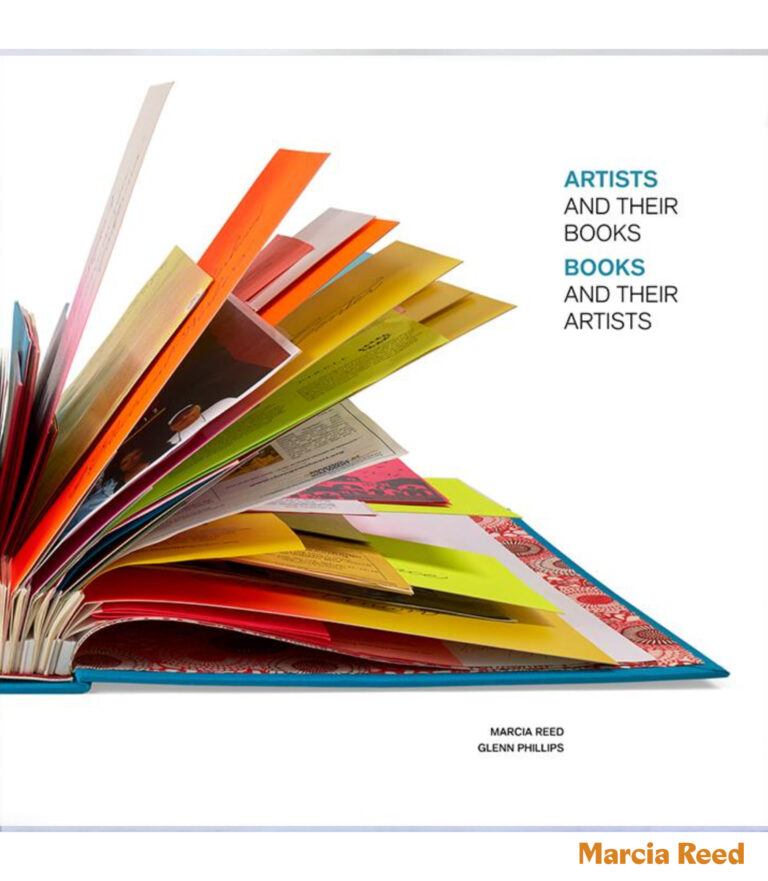

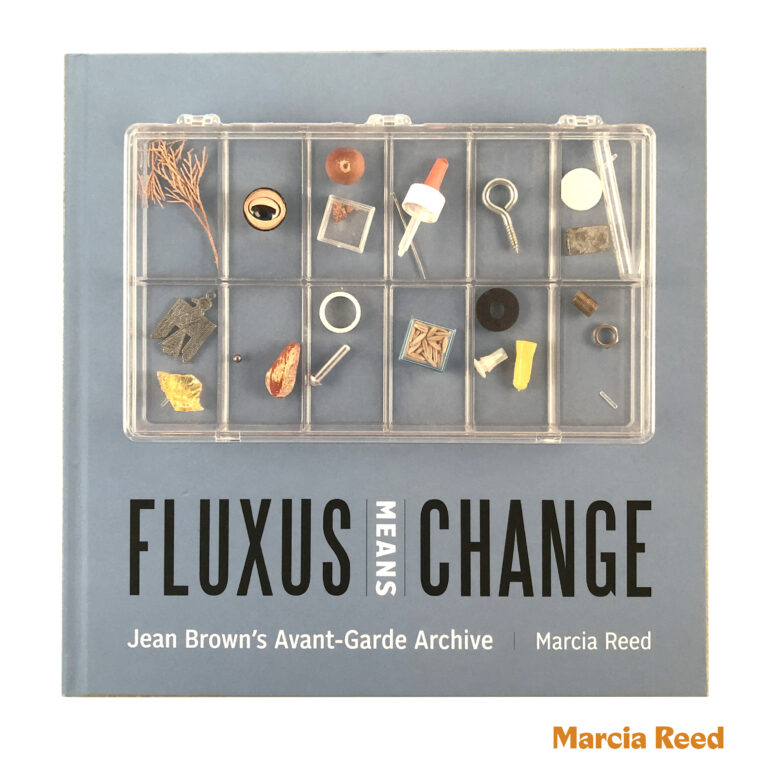

Marcia Reed

Presently Chief Curator and Associate Director, Marcia Reed has developed the Getty Research Institute’s collections since its founding in 1983, acquiring many of its notable rare books, prints, and archives. Her award-winning catalogue of the GRI’s artists’ book collection Artists and Their Books, Books and Their Artists, co-authored with Glenn Phillips, was published in Summer 2018 to accompany the exhibition. Her most recent publication is a catalogue for the GRI’s September 2021 exhibition on Dada, Surrealist, and Fluxus works: Fluxus Means Change: Jean Brown’s Avant Garde Archive.

Susan Sironi

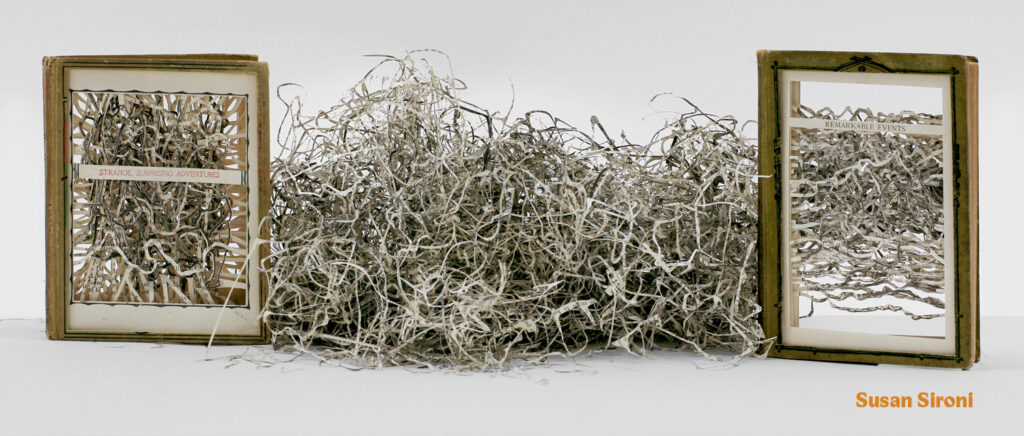

Susan Sironi is a Los Angeles based artist. Since 2003 she has been using found books as a medium for her work, deconstructing them to emphasize the importance of how we communicate and what form it may take. She had her first solo show at Offramp Gallery in Pasadena in 2008. She has exhibited throughout Los Angeles as well as nationally and internationally including Craft Contemporary Los Angeles and the Carpenter Art Center at Harvard University Cambridge.

Now Be Here

Now Be Here exists to achieve equity for women-identified and non-binary artists in the field of visual art. Conceived in 2016 by Los Angeles-based artist Kim Schoenstadt in response to the dearth of women-identified and non-binary artists in museum and gallery exhibitions, Now Be Here documents and supports the depth and breadth of this dynamic community. Beginning with large group photographs, it now encompasses a visual artist directory website that serves as a conduit between the general public and artists and develops programs that promote them to new audiences. The Guest Curator Initiative seeks to enhance the connection with artists featured in our directory through a thoughtful engagement with the themes, processes and contexts that inspire and inform their artwork. The program invites curators and scholars to discuss relevant aspects of an artist’s practice through a recorded, live or written conversation. Created by Patricia Ortega-Miranda, who is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Art History & Archeology at the University of Maryland, College Park, where she specializes in 20th-century art with an emphasis on Latin American art and culture.

Pre-Talk Conversation

Johanna Drucker Some of you know me and some of you don’t but Kim was encouraging me yesterday to be difficult and confrontational, and I said “I’m trying to change my reputation!”.

Kim Schoenstadt I want a juicy conversation. I want to get into the weeds.

Johanna Drucker I think we’ll start by asking each of you just to say a little bit about your relationship to books and artists’ publications. So that, for folks who don’t know who you are and what your engagement is.

Marcia Reed Can you give us a time limit? How long do you want us to talk?

Johanna Drucker I think Kim laid out for you how we see the event as a whole, and I think by the time we gather people together and Kim does an intro we’ll be about seven minutes into the hour, and our goal was to wrap up the initial part of our conversation just before the end of the hour, and then leave room for questions. And if at the point there are no questions, I’ll start poking at you with things like “Books!?’ I think the initial statements should be in that two minutes, really capsule, what do you do, why are you involved with books, just so that people have a glimpse of your personal profile, but that will keep coming out because I’m going to ask you more questions you about your view or your work, or how you see your role in relationship to artists’ publications. You will speak from a combination of personal experience, professional point of view, and your own passions. We do share an interest in books, but we probably all have very different ideas about all that and what it means, and what it’s for, and how we’ve come to this.

The goal here is to address one of audiences today, the women who are part of the UCLA Center for the Study of Women. They don’t know much about artists’ publications, but they’re very interested in issues of activism, social justice, the way in which cultural transformations can be affected by different kinds of activities from production to curation to reception to intervention. So, again, I’m thinking to whom are we speaking to? I hope in part we’re speaking to women colleagues, students, and the general public for whom these ideas could be inspiring but also informative. So I don’t assume a lot of prior knowledge, but we’ll have people who have deep specialized knowledge who are in our audience, and then we’ll have people who don’t. A couple of my students who are showing up from the Information Studies program, and these are people who want to be the future curators, so what are we saying to them? What are we trying to offer them as ways of engaging with fields that we know well.

So, that’s my vision of this, does that sound good to you? Is there something else that you’d like to stick in?

(sounds of agreement)

Johanna Drucker Again, it’s a quite diverse panel in terms of experience and point of view and where we all come from. So, it’s interesting…

Kim Schoenstadt One thing that I want to throw out there that I found interesting going through everybody’s slides and putting together this super-last-minute Powerpoint—which, by the way, thank you everybody, it looks great—is that it is fascinating to me to see how, Susan, you’re very meticulously disassembling books and you’re very purposefully deconstructing and how Tia is very purposefully constructing from the ground up. We have one artist on this panel who’s choosing paper, choosing type, setting type, very carefully assembling a book, and …

Johanna Drucker There’s two of us!

Kim Schoenstadt Sorry, sorry, and then Susan, you’re totally ripping it apart, exploding it back up into something else, like a new light from that…

Susan Sironi I definitely feel like a frog among gazelles here. I am just like “what am I doing here?” but I am, I think there is something maybe I can add because I think that when you destroy something, you become very intimate with it, and I have had this whole month to look at everyone’s work here, and I am just dumbfounded. I feel lacking that I didn’t know about Johanna’s work or Tia’s work. I know Alexandra’s work because she’s in LA and I’ve gone to a couple of her shows. So, for me, this is absolutely terrifying. I’m not a big talker so I’m trying to use this as a way to empower myself and to look at how all you women are empowering other people through your teaching, through the books that you make, it’s … I’m going to try not to fade away, but I struggle with talking.

Johanna Drucker Well, we’ll invite you to speak and make space. It’s important. And I’m thrilled that Marcia’s here because again what a whole other view you have of this field and we won’t try to figure out who’s been in this field longer, but we both…

Marcia Reed Yes, thank you.

Johanna Drucker We both know a lot about all of this and have watched it for a long time and I would not want to have the responsibility that you have.

Marcia Reed Well, I kind of distribute it, that’s how you do that is you try not to do it all and take all the credit. I guess because I worked with others. Yes, they were men, of course, men who wanted to take all the responsibility, be the deciders on collecting and things like that and really talking. This really taught me that it isn’t where you want to be, and it’s not the kind of collection that you want to make. And Johanna and I have known each other, I don’t know how long actually, decades.

Johanna Drucker Thirty years at least.

Marcia Reed Yes, but we’ve always agreed not to disagree; we have great respect for each other, and so we have these really good conversations and then kind of listen and that’s great. I got to know Tia because we were both jurors in the pandemic year of Minnesota Center for the Book Arts, and you make strong statements too Tia and that’s great. It’s really great if people say, “Well I think this,” or, “I don’t think that works,” or something like that. But then when you’re collecting for an institution, it’s good to bring in many perspectives. I’m really proud of the fact that at the Research Institute, there maybe seven or eight curators collecting artists’ books and not directed in any way, but as appropriate to the kind of books they’re collecting and then sometimes art and culture they wish to document. This is interesting for me to oversee, to kind of watch that schoolyard full of people interacting and make sure that it works well. That’s what I think you should do, have lots of voices, that’s the way you collect.

Johanna Drucker Yes, and we’ll come back to that point I think because the role of institutions and the challenge of a field that really has very few gatekeeping mechanisms is also something to think about, the benefits and the liabilities of that because it’s very different from the mainstream of visual art in that regard.

Marcia Reed I’m having a really good conversation with a dissertation student in New York, and I think some of you might know her, her name is Na’ama Zussman.

Johanna Drucker Oh I know her.

<overlapping conversation>

Johanna Drucker Oh, I’m on her committee! <laughs>

Marcia Reed Yes, but the conversation we’re having is going into how does an artist’s book perhaps change when it goes in the institution because the institution is determining it by the way it catalogs it, by how it’s shown, by its collecting context. And I had never really thought of that and I’ve been having these great pandemic conversations with her just because we had some time and I never…

Johanna Drucker Yes, she is interesting.

Marcia Reed Yes. But that idea of an institutional determination of an artist’s book, I’d love to talk to some makers about that or if you could bring that up about…

Johanna Drucker Yes, I’ll bring it up.

Marcia Reed How do you feel when your book goes to an institution that maybe wasn’t even in your favorite place or a collector?

Johanna Drucker Right. No, exactly. There’s lots to talk about there to be sure. And since you’re bringing this up Marcia, I’m just going to build on that for a second and ask each of the other folks here if there’s any particular issue that you would like to have touched on, so that you can talk about it? The list of things that I have here have to do with why books, relationship to gender, changes in the field, the books as a symbolic artifact, perhaps impact of the digital, what it means to think in the book format, issues of social justice and activism. Those are some of the thematics I’d like to touch on, and I think this whole question of institutions and their role and curatorial judgment and engagement. Is there anything else that you would like to have brought up? How about you Susan, is there a theme or a topic? When I look at your work, I think a lot about the book as a cultural icon and a historically resonant artifact, but is there anything that’s particularly relevant to your work that you’d like me to bring up?

Susan Sironi I don’t know, I mean with each of the questions as I was looking at them, I was always having to look at it from a person who doesn’t create books, that I’m basically reinterpreting them and disassembling them. So, I guess I really don’t have something else that lingers. I get curious about distribution issues, but that’s going to go back into your discussion of where the book finally gets placed and who has access to them, and is that access where we want our message. Because activism is kind of a grassroots phenomenon, and even I know that my books wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for a gallery to show them. So, I think it’s going to be covered.

Johanna Drucker No, but I like the focus of that, just making sure that issues of distribution and access do get brought into focus at some point would be good. How about you Alexandra?

Alexandra Grant One of the concerns I have is we’re starting a new line called X Topics and we’re really focused on how do we work with artists who aren’t already in the center in some way or marginalized, and X Topics will be focused on artists of color curated by two curators of color. And as we began that project, we realized that even to invite an artist to make a book, that we had to consider economic questions that were beyond… …make the book, how do we rethink bookmaking for people who haven’t had access to making books as collaborators? But it’s a holistic question and a more feminine question of how these books, and obviously we’re really excited to be working on these issues.

Johanna Drucker It’s a different access…

Alexandra Grant I think you have to talk about money I guess, not only like sexy topics, money, distribution, but how that works in relation to gender, race, and class. I think those questions are super interesting and quite surprising. Yeah, so it’s like a holistic picture of how books will fit into giving—we do a lot of lip service in American culture especially about giving a platform and wanting to support people, but what does that really mean, and it’s the least sexy thing which is giving people—being in Berlin I really feel the difference just immediately that people have dignity because they can afford their apartments, they can afford to not work 17 jobs and there’s that opportunity to be able to lie on the couch and do the kind of thinking which requires zoning out without economic concerns of poverty. And I think that that question—I don’t like the idea of talking about money in the sense of money determines creativity, but I think we have to, we must as part of our feminine approach to supporting other people.

Johanna Drucker There’s no social justice without economic equity, it just…

Alexandra Grant Boom!

Johanna Drucker Right. Now Kim’s going to shoot me because I’m getting you all to say all your wonderful stuff before the panel starts. But we’re about to start.

Kim Schoenstadt No way, now we have rapport, now we have…

Tia Blassingame Weren’t we recording this?

Johanna Drucker Oh, we are recording it actually.

Johanna Drucker I know that Addy [Rabinovitch] is going to make us start, but do you have any topic that you want to make sure I touch on that you can say in about two seconds before we go on because I don’t want to get Addy mad at me too?

Tia Blassingame I know we have such a short amount of time and I feel like we’re touching on a lot of things, I think we’re good.

Johanna Drucker Okay.

Addy Rabinovitch I’m turning my video off and I’m starting the webinar.

Public Discussion

Kim Schoenstadt Welcome everybody to this amazing discussion, I’m very excited about it. Thank you for joining us. First let me thank our cosponsors, Scripps College, the UCLA Center for the Study of Women and especially X Artists’ Books for running this Zoom and especially Addy Rabinovitch and as well our brainchild of the entire Guest Curator Initiative Patricia Ortega-Miranda. Special thanks to the University of Maryland Art Gallery for their support of the Guest Curator Initiative and the Now Be Here project.

Second, I would like to do a little bit of housekeeping, we will be recording this conversation, it will be posted on our YouTube page and transcribed as well. The transcription will be available on the Now Be Here website in a few weeks and we will announce via our socials and mailing list. We encourage you to post questions as they come to you during the talk. We will read the questions at the end of the conversation. And for those of you not familiar with the Zoom format, I have made this little guide here so you can see how to post a question. There should be a Q&A button at the bottom of your screen which you should be able to see here. Johanna Drucker will be our moderator for this conversation and after a round of introductions, I will happily hand it off to her.

I’m going to go in alphabetical order of the panelists:

Tia Blassingame is a book artist and print maker exploring the intersection of race, history and perception often incorporating archival research and her own poetry in her artistic book projects for nuanced discussions of racism in the United States. In 2019 Blassingame founded Primrose Press, The Book Print Art and Scholar of Color Collective which brings book history and print culture scholars into conversation and collaboration with Black, Indigenous, people of color who are paper makers, book artists, curators, letter press printers and print makers building community and support systems. Blassingame is an Assistant Professor of Book Arts at Scripps College and serves as the Director of Scripps College Press.

Johanna Drucker is Distinguished Professor and Breslauer Professor in the Department of Information Studies at UCLA. She is internationally known for her work in the history of graphic design, typography, experimental poetry fine art and digital humanities. Drucker’s artists’ books were the subject of a traveling retrospective Drucker Works, 40 Years of Books and Projects in 2012 to 2014. Her new titles include Visualization and Interpretation, MIT Press 2020, Ilazd: A Meta Biography of a Modernist, Johns Hopkins University Press 2020 and Digital Humanities: An Introduction to Digital Methods which will be published by Routledge in 2021.

Alexandra Grant is a Los Angeles based visual artist who examines language and written text through painting, drawing, sculpture, video and other media. Her work has been exhibited at the Orange County Museum of Art in California, Contemporary Museum, Baltimore Maryland, Los Angeles County Museum of Art in California, The Center for Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv, Israel and The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles among others. She’s received the COLA Individual Artists Fellowship and a grant from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation. She is the creator of the Grant Love Project which raises funds for artist-based nonprofits such as Heart of Los Angeles, Project Angel Food, Art of Elysium, 18th Street Arts Center and LAX Art. In 2017, Grant cofounded X Artists’ Books, a publishing house of artist-centered books and has published eight literary works of art to date and will be releasing six new publications in 2021.

Marcia Reed is presently Chief Curator and Associate Director at the Getty Research Institute. Marcia has developed the Getty Research Institute’s Collection since its founding in 1983, acquiring many of its notable rare books, prints and archives. Her award-winning catalog of the GRI’s Artists’ book collection, Artists and Their Books/Books and Their Artists coauthored with Glenn Phillips was published in the summer of 2018 to accompany the exhibition. Her most recent publication is a catalog for the GRI’s September 2021 Exhibition on Dada, Surrealist and Fluxus works, Fluxus Means Change: The Jean Brown Avant-Garde Archive.

Susan Sironi is a Los Angeles based artist. Since 2003, she has been using found books as a medium for her work, deconstructing them to emphasize the importance of how we communicate and what form it may take. She had her first solo show at Offramp Gallery in Pasadena in 2008. She has exhibited throughout Los Angeles as well as nationally and internationally including Craft Contemporary Los Angeles and the Carpenter Arts Center at Harvard University, Cambridge Massachusetts.

Welcome one and all and from here I will hand it off to Johanna.

Johanna Drucker Thank you. Thank you, Kim, and thank you Patricia, the behind-the-scenes organizers and instigator of this event. I appreciate your having involved me in it, and I am honored to be able to be here with these four artists, women, curators, people involved in books and I’m going to start right away by asking each of them if they would like to say a couple of words about their involvement with books, artists’ publications and with an eye towards giving you a sense of their individual profiles, but also focusing on why books now, what’s important, I mean on some level we just saw a wonderful slide show in which we saw books taken apart, put together, used as activist sites, used as theatrical and gallery items, also used as intimate items. So, we say the word book and we think it means one thing, it means so many things and we’ve just seen this tiny little glimpse. So, if each of you could just make a short statement about your own relationship to this complex category we think of as books from an artist’s point of view. So, Tia, I’m going to start with you and I’m going to follow the alphabetical order in this first round and after that it’ll become much looser in format. So, Tia?

Tia Blassingame Sure. So why books? I mean when I think artists’ books, I think they’re extraordinarily kind of endlessly mutable and can kind of take in anything and be combined with anything whether processes or content. I also think everyone has some relationship with books whether growing up your parents read to you or they did not, you had books around you or you did not, so I think we already have some kind of relationship or memory or longing related to books as physical objects, as containers of information. I think for me personally as an artist, I mean I just think in the book form which sounds weird I think to some people, but it makes sense to me I think because books have always been around me in my life. And then in teaching I just see students, they have things to say and sometimes they’re challenging things to say or things that they’re trying to work out, and it can give them a way to express themselves and have a moment with an audience that may not typically listen to them.

Johanna Drucker Great. Many topics there for us to pursue in a few minutes. Alexandra?

Alexandra Grant For me artists’ books, in particular, are seeds, I mean they’re interdisciplinary spaces that—you know, our first year of publishing books, we published three or four and three of them were performed, “The Words of Others,” “High Winds” and my brain is going blank, but I’ll come back to it. But what really blew me away was the fact that so often when I work with an artist, I’ll say, “Okay, imagine this as an exhibition between two covers, imagine what this can do to transform your career, imagine what spaces or get-togethers or gatherings or collaborations this book, this seed that we’re planting, will bring.” And, inevitably, it does. And I think we have the imagination of the book as a haptic experience of something that we can examine privately in the space of our library or of our homes, but in fact they’re these incredible sites of transformation, we also become transformed by the intimate family of collaborations that happen in their making and in that imagination that— “High Winds” for example by Sylvan Oswald and Jessica Fleischmann became a performed play with musical elements and that wasn’t the intention, but it was so clear that that’s what the book should be, so I love that idea of book is seed.

Johanna Drucker Terrific.

Alexandra Grant “The Words of Others” is the last book.

Johanna Drucker Thank you.

Alexandra Grant And we published it at the Getty. Marcia Reed, don’t hold it against me, but we did it for Pacific Standard Time. <laughs>

Johanna Drucker Marcia, why don’t we see what your thoughts are about books, artists’ publications?

Marcia Reed So I’m not an artist, I’m a curator, collector. I was an art librarian, I was so happy when I was going to graduate school in librarianship art history that there was this thing I could do with art and books. But I was dealing with older books and the interesting thing that in thinking about today, I realized that older books, the history of the books, the history of printing and things like that is a very masculine history and women kind of seep in, the widows of the printers and things like that. I think what activated me was getting the Jean Brown collection of Dada, Surrealism and Fluxus, artists’ books, mail art, concrete poetry. She was a very wide-ranging confident collector, and I was at the Getty, this was in 1985, and I thought, “Well we need to think about how to make this work for the Getty.” And I knew that there were a lot of East Coast collections, there were some West Coast collections as well, UCLA had one and I thought, “How can I make this work for art history, how can I make it work in an art library in a special collection and try to broaden Jean Brown’s vision of the collection so that it would feed into a collection on art history?” So that’s been kind of a mission for me is not to sideline artists’ books as over there, but to put them in as part of the history of the book in the twentieth century and then the history of contemporary art. Because so many contemporary artists engage with the book, maybe they make only one book and maybe they’ll be taken by it or maybe they’ll make it as part of a graphic practice of their own, but to make artists’ books be part of art history. So, I think that’s probably the most important thing I thought was important to do, to see Dürer, to see Vasari, and then to see contemporary artists’ books.

Johanna Drucker Right, right. So much to talk about there, the many historical dimensions and also disciplinary intersections. I look at Tia’s work and I think about literary traditions and the traditions of voice poetics as well. And I mean, Alexandra is an artist who uses language and of course this means we’re cutting across disciplines here and the books do that in many ways that are both challenging and rewarding for their use and their production. And Susan, your work also adds a whole other dimension here. Do you want to say a few things about what your relationship to books is and what your specific engagement as an artist is?

Susan Sironi Yes. I remember in the early 2000s going to thrift stores and library sales and books were being thrown away by the truckload and I was just—I didn’t have a lot of books as a kid, so I saw this value, I saw these incredibly beautifully illustrated hard bound, gorgeous objects being discarded, even if I didn’t think about the content of what was inside them, they were beautiful objects and they were just…so I collected them for a couple of years and just sat on them. And through a kind of a frustration with how I communicate with the world, I was able to use the book to bounce off of, suddenly I could do something to this book that said something that I was having a really difficult time either admitting to myself was an issue, and it was a quieter process like what Alexandra said. I could do it at home, it wasn’t something that I thought I had to share with anybody, so I could do it very slowly, very carefully, meticulously. And then once I realized I did have something more to say about culture, history, feminism and books were just overwhelmingly part of the nomenclature that was to me influencing everything we did, so I took the approach to, instead of making my own because that seemed overwhelming, it just seemed like what it would take. I would just take apart some of that history, kind of rearrange it, control it a little bit. So that was pretty much how I got involved and why I like them. They’re physical objects, they’re kind of like yoyos, you know what you think they can do, but all of a sudden they can do crazy things in the right hands. So, it’s just been a gradual increase in excitement over the book as an art form as opposed to a deconstructed sculpture that I want to manipulate.

Johanna Drucker Fabulous. And if people were here for the slide show and got to see the kind of visual richness and complexity that you engineer through your aesthetic interventions, they’ll appreciate the many reverberations that your words have in the objects, I think. But you also brought up, thank you for doing so, the concept of feminism here. And I’m just going to throw out and I’m not going to orchestrate the responses, I’ll let you all speak as you like and it’s the question of gender, to what extent—I mean I’ll confess, as a child I was always writing, scribbling away, I thought, “If I’m a writer I can escape my gender.” No, I mean that was a formula, it was the 1950s, right? So, it’s like, to me, it wasn’t something I could embrace and kind of run up a flagpole because it was kind of early days for feminism let me tell you, and so the question of gender and gender politics and identity politics, how does that relate to books and our work and our institutional roles and our creative identities and the worlds we work in? If I say, “Why books as a woman?” or, “Why artists’ publications from a gendered professional or personal creative point of view?” Is there something to be said there?

“I think about books or artists’ books and independent publishing as control and maybe also access…”

Tia Blassingame I’ll jump in. I mean, I think about books or artists’ books and independent publishing as control and maybe also access, I think maybe if I went to a commercial publisher, they would not be interested in what I have to say or the ideas that I’m promoting, right? Maybe it would be because of the content, maybe it would be me as I present and so I think about how it gives me control within my process, kind of absolute control because I’m a control freak, so I can select everything and I can make the paper and on and on and then thinking for students, as well, it gives them some control as well.

Alexandra Grant I definitely want to know if Tia is Virgo, but I’ll ask that later.

Tia Blassingame How did you know? <laughs>

<overlapping conversation>

Alexandra Grant I have no idea … But I’m making this a—all Virgo science, there’s a lot of Virgos in book publishers.

Susan Sironi I’m a Virgo.

Alexandra Grant Oh my god.

<overlapping conversation>

Johanna Drucker Half of the audience is raising their hand…

<laughter>

Alexandra Grant I really am interested in the idea again of being marginalized I think really in relation to Tia’s sense of control, it’s that sense of providing a space of dignity which I think owning your voice, being able to articulate it as an image or a text or in combination and then creating a safe space for that. And from the history of zines, which just involve being able to photocopy, that you could make an artists’ book for a small amount of money and that you could distribute it by handing it out for free if you wanted to or that there was this sense of that you could stand in sort of creative artistic dignity. And so, Johanna I know that you want to talk about social justice issues, and I think feminism is definitely one of owning your voice. Now I came to writing and this is a very Cixousian way to say it but through the writing of Hélène Cixous, the idea of how do we examine how language speaks us and how we as women or female identified humans can really examine authorities present in the languages that we inherit. And so, book publishing is a way of moving from the theoretical into action and so just the act of showing up in a body that is not centered in controlling discourses is radical, which is why I like to encourage people to publish, to take that first step because it is available.

Johanna Drucker I think this transfers into institutional roles in politics as well. So, I’d be interested to hear Marcia address that if you feel like it or from your point of view of observing a huge field in which you see all kinds of different people and identity politics playing out in artists’ publications. You have such a big view, but you also are embedded as an individual with your own history of gendered politics I’m sure or I would imagine, I’m not sure of anything, but I would imagine. But is there an issue here, I’m just curious?

Marcia Reed Well, I think the direct communication and the owning your words instead of somebody editing, illustrating, designing something that you maybe don’t recognize as yours. And it’s an interesting thing, we have a couple of people actually, Johanna and Tia who are in academic positions and I was thinking as you were talking that you do publish different streams of books, you come up for tenure. I’m not really sure how artists’ books count or don’t count for tenure, I can wonder a bit. I heard someone in I think it was in a recent college art talk about how her anthology of Basquiat work didn’t actually count for her tenure considerations, that it wasn’t seen as her original work and that’s the kind of artists’ book. But it is interesting that you have to have different professions and do what you feel like you need to do no matter whether it’s going to be credited or not. But then, as we were talking about before, we talked about you need to have the base, you need to have the money to be able to do your artists’ books. So, this is a very rambling answer to that question. I think the thing that impressed me the most about curating the early avant-garde books and then moving through artists’ books and other kinds of productions, say mail art, which was never seen as anything other than a shared project, it wasn’t really a publication, but that those were things that were put out there to share, to give to people, to put ideas out there in the world and it’s actually been rather successful, those ideas are out there in their artists’ books, in their Xerox works. And so even though that wasn’t the goal, it’s seen now by collecting institutions like mine or like some of the other large collecting institutions as part of the history of art history, of feminism, and of other areas of social activism. And the other important thing is the multi genre work that’s there, so it’s writing, it’s poetry, it’s photography, it’s design, it’s making paper, it’s maybe going back and taking other books and putting them out there again in a new format. So, I’m sorry, this isn’t a well composed answer.

Susan Sironi Johanna, I’d just like to add that we’re all also, besides issues of control, we are looking at empowerment and just the physical act of printing a book, it gives you internally something that says, “I can do this next thing.” Maybe this one’s a small edition, but maybe with time and with smaller or greater community support we empower ourselves and we give ourselves that confidence.

Johanna Drucker I think that is so crucial, Susan, and I’d like to come back to something that we were talking about before we started the public part of the program which has to do with access to the means of production and what it means to be enabled to make a work. And I’ll just say the first time I printed a book which is back when dinosaurs roamed the Earth, there were no digital output technologies, if you wanted something to be in type, you had to hand set it and print it or else you had to go to a service bureau and pay for photo set type, which was way, way beyond my capabilities. So, the cultural authority of printing a text that was rendered in type form that looked like a real book, I think was so profound and all it took at that point was my time, but I could afford my time. And I think, Alexandra, we were talking about what it means to have access to opportunity, it’s not just means of production, you used the term holistic, and I wonder if you’d like to just go back to that because it was a very interesting approach.

Alexandra Grant Thanks. So, at X Artists’ Books we are starting a new line of books called X Topics that will feature artists of color. And the first year we have two curators, Anu Vikram and Ana Iwataki who’ve selected three artists. And as we structured how this would work, we really wanted to not only award sort of a book deal for an artist to expand upon a vein of thought that they wanted to explore, but we realized that for the artists, in order for them to do the writing, we had to help them afford their own time. And so we began thinking about making an artists’ book as again a holistic picture where an artist is afforded the dignity of reflection, to be able to reflect you have to be able to sort of, you know, in this Philip Larkin sense, how long does it take to write a poem? Six hours—five hours on the couch and one writing. You needed to have that invisible time to be able to reflect, to create, to articulate. And so I’d love to hear from Tia as well, because I feel this is something you’re an expert at, but how do you create a safe place that’s economic, that’s intellectual, that brings in space for a difference into an editorial process, a collaborative process? I’d love to hear.

Tia Blassingame Yes. I mean I think of Scripps College Press and the book arts classes, part of it is we don’t know one another, students are coming from different disciplines, 99 percent of the time they’ve never set type or any of that although increasingly I’m hearing about high schools where they’re setting type, and I wish they had been around when I was in high school. But typically, they’re sort of fired up and they have something that they want to get out there, but they don’t know how to do it. Sometimes it’s personal, sometimes it’s coming from a point of trauma, right, and if you’re in a space with people you don’t know, how do you trust them, right, how do you trust that the critique that they’re going to give for your work is valid and is coming from a place of respect, right? And so I think that’s challenging, challenging in any setting, in any sort of discipline, but I think for me it’s starting to build up how to critique work and see work and also value everyone’s work even though the end result might look completely different from anything that you were interested in, but that you’re going to be involved in their process or present in their process which is really hard, I think for me that’s very hard, and I actually don’t like people being part of my process, partly because I’m dealing with memorializing people, et cetera, and I just need more space to determine what that’s going to look like. But I think for a classroom setting, I think a lot of it is learning how to critique work and hear one another and be part of the process.

Johanna Drucker So Tia, I’m going to follow up there because I think you’ve raised a set of points that are really interesting and central here which is that there’s a kind of intimacy and privacy to the making of a work. And again, Susan I think about your work and I can sense sort of like it’s here, there’s a kind of safety to that. And then there’s the question of exposure and there’s a kind of built-in paradox here which is we make books as intimate objects but they go into a public life afterwards or have some kind of reception to them. And I wonder if there’s a sense of how one thinks about the life of the book after it’s launched, right, and where the anxieties are, the questions of reception and control and if something is received, does it need to be received with an understanding of who that maker was, who the audience is, who the author was or not and how do we attach that identity to the object in a way that helps it be received in ways that are, I’d say, what were you saying Tia is a kind of empathic criticism or respectful critical approach. So, tell me about reception for your works and what are the venues and issues. And again, for you Marcia, I see you receiving so many—seeing so many things and then having to sort through, “Well what am I seeing? How do I know what it is when it comes as an autonomous object no longer connected to Tia, Alexandra, Susan?” and so forth. So, I’m not sure if I’ve posed a clear enough question for you to answer it, but <laughs> thoughts on all that?

Susan Sironi Well I’ll start. If I have my choice, I’d keep every book I ever cut.

<laughter>

Susan Sironi I do not like letting them go, but that’s kind of not the reality of if you want to put yourself out in the world as an artist, so I let them go, I try to price them so that if anyone takes them on, it’s a significant investment for them. It is hard to imagine that anyone is going to see them the same way that I see them and when I feel like they do I am ecstatic, I’m so excited and now they have a good home, I hope they have all good homes. So, I’ll just put it out there that way because it was real tough in the beginning. I drove some people crazy.

Johanna Drucker Yes, you’re much more optimistic than I am, I believe my work circulates in vast networks of misunderstanding.

<laughter>

Johanna Drucker What about, did you guys have something you wanted to—issues of reception and so forth? Tia, did you want to say something or Alexandra or Marcia?

Marcia Reed You know, it is a lot like collecting art and art goes out there—the other great thing about books is they live longer than we do just a reminder about this <laughs> is they’re going to be around and we may or may not be. We were talking before about this, I’m really proud that there are I think 11 curators at the Getty Research Institute (not the Getty Museum, but the Getty Research Institute), and there are about seven of them now who are collecting artists’ books that relate to their areas of Latin American collections, African American collections, architecture, many different types of collecting that go together with art history. And so, I think that’s really important as with other books, books appeal to many different people for many reasons and some of them do or don’t have direct connections to the author, the maker’s intent, but I think the books—this is one of my mantras really is that books have lives, and they’re not our lives. They go out there, and I think art does too. And people will have different understandings and like children or other things, you have to let them go.

“Books have lives, and they're not our lives. They go out there...”

Tia Blassingame I’m just thinking over the last year during the pandemic—are we out of the pandemic yet? Probably not… But, pretty much, trying to teach studio courses online, and so having students make artists’ books, their first artists’ books and we’re not together, which I would have said a year ago was crazy, but I don’t think it is because they made amazing work. But we weren’t together around a table, we didn’t handle the work, so how they sort of document the work becomes kind of another artists’ book whether it’s a video or photos or a GIF or I had a student who made the work and then destroyed the work, it was very personal, trying to sort of deal with a certain very negative relationship and just destroying it, so if you watch the video of the work being destroyed, you might have had access to a page or two or some of the text, but that wasn’t the point, it wasn’t for you, it was for them to sort of process. And so I love what Alexandra said about looking at artists’ books as seeds and they can kind of go anywhere. And for many years I tried to kind of explain that the book could be anything and it could be a performance and I feel like students never maybe took me seriously or that was too challenging, and we’re also in this structure of needing to get a grade, right, so is the performance going to get a good grade or not. And I feel like within the digital space, students experimented more and were able to let go in a way that they wouldn’t have if we were in person. But for my own work, thinking about reception and whether it’s understood or misunderstood, I think content-wise it’s understood, but not what I’m trying to do with the work where I’m trying for each book to have a relationship with the viewer and to sort of change the viewer, and I think that typically is not really understood and maybe I don’t express it enough, it’s not explicit enough. But that’s all right, I feel like the book itself is doing its work and whether you implicitly understand it or not, it’s still doing what I’m expecting it to do.

Alexandra Grant I want to add to what everyone has answered with a vision or a memory that seems a little bit like a dream. I mean Johanna your idea of your books circulating in misunderstanding I think is just so wonderful, but that idea of the recipient of the artists’ book misunderstanding is actually part of the act of the artists’ book. In 2006, Glen Phillips invited me to be part of a show he curated at LACE, I think it was called Draw a Line—Glen if you’re here, forgive me—but we were invited to go to the Getty Research Institute and to go to the library and research the Fluxus collection.

Marcia Reed Yes.

Alexandra Grant There’s so much protocol and it’s very formal, and I remember being taken for the first time to this wonderful library and there are all these scholars looking at Pirandello drawings and Dürers with white gloves and everything is very, it’s just—it feels improbable to be there. So what I had asked for arrived on a tray and I remember the first book I opened was full of sand, and the sand somehow got over the table and I had this absolute anxiety of misunderstanding of like, “Oh my god, everything is so clean and somehow I have a book of full sand and the sand was the intent—” that was the intention, so there I was 40 years later receiving this artist’s book exactly in my mind how the artist had anticipated, which was to defy the expectation of what a book was. But it was just this wonderful—it felt like a dream. But also, I went from extraordinary anxiety to almost laughing out loud that I had found myself in a situation and the joy and improbability of it made me realize that artists’ books had this freedom to put sand in a box, that was part of it. And then the radical idea occurred to me that, “Wow, this library is such a special place,” right, that the inclusion of this work blew my mind, it expanded my idea of a book, it expanded my idea of being a reader, a receiver and it gave me an incredible sense of freedom of what it meant to be an artist, to be all these decades later still thrown in the best sense by this work.

Marcia Reed One thing I should say is a really great part of my job, and I think you were working with Glenn Phillips who is my coauthor on the artists’ books project, is that it is so much fun to show people books. And this is a really funny anecdote, I was working on the Jean Brown catalog and Ian White was brining Dave, Dave Hammons, to our collection to look at artists’ books and he said, “Could you show him?” And I was like, “Yes, I would be happy to do that.” The things I have behind me in this screen shot that I’m using as a background were some of the things that just happened to be on the table. I had the green box out, I had the Boîte [La Boîte-en-valise] out, just happened to be working on Marcel Duchamp that day and I didn’t know that David Hammons is—I knew—I learned quickly. And so, you have these moments where people just—it’s like an electric connection or something and it is great to have these serendipities when you just show people what you’re working on, or we happened to be working on our alchemy show when Anselm Kiefer came by and he came to see the Cave Temples of Dunhuang, he was interested in that simulation of them. But then we just happened to mention the alchemy things that another curator, David Brafman had out and Anselm was supposed to go back and take a nap for his lecture, but he didn’t do that. He went and he looked at the alchemy manuscripts and books which are magical. And so, to show people from little kids, from little kids who came to the show on the Dunhuang Caves, the first graders to well-known artists, anybody, is just so much fun because you never know what kind of a response you’re going to get. And I love to do it with artists’ books because I think [people] probably don’t know so much about them. So, I have to say that’s a very special part of my job to say, “Look at this,” like you did Alexandra.

“I totally believe in that making a book itself is a transformative act, there's an authority that comes with that, but there's a lot of rhetoric around books as change agents.”

Johanna Drucker These are great stories, they’re wonderful. And it brings me to a question about how books work as agents of change. I think there’s on the one hand from the legacy of the avant-garde across the 20th Century a sense that that kind of moment of shock, the de-familiarization that that can produce transformation, right, it can motivate political action, it can motivate changes of consciousness, but there’s also, so we have that whole tradition, right, and there’s a big adherence to that tradition that art is supposed to be the political conscience of the culture and do this transformative work, and I have my feelings about that on all sides of the spectrum. But then I think about just the fantastic power of aesthetics, the fantastic power of something simply to engage and transform through the experience it offers, right, I think of the tonal values, Tia, on the pages that were in the slide show and just what that does to my perception to have to look at the tonal values on a sheet of paper, right? And that’s independent of any particular message or so forth, it’s like, “What’s that?” so I guess I’m asking you do we believe in books as agents of change and if so, what, I mean, look, the world’s broken and it needs to be fixed folks, there’s no question about that, right, but the question is what do we see in the transformative possibilities of books? We’ve talked about empowerment for individuals which I totally believe in that making a book itself is a transformative act, there’s an authority that comes with that, but there’s a lot of rhetoric around books as change agents and I’m just curious about your individual thoughts about that, or not. <laughs>

Tia Blassingame I mean I believe that. I feel like I have to believe that. So, the Book Print Collective—we have a longer name, it’s too cumbersome, so we’ll just say the collective I started—I feel like we’re coming together kind of around the notion that artists’ books have the potential to bring us together, some form of racial unity, something. And I feel like that’s possible, and I kind of have to feel like that’s possible because for me artists’ books are what I use to hopefully educate to sort of push people forward to something better. Yeah, I think where I am right now is that I have to believe that. I mean I feel like I’ve believed that for a while, but in this moment I have to believe that.

“I like the idea that you always want to give people alternatives to what is mainstreamly available.”

Susan Sironi I like that, we need alternatives even if it’s not a big thing. I mean when you’re a kid and you like experience Mad Magazine for the first time, you’re floored. There’s an alternative, there’s an alternative to Disney, there’s an alternative to the expectations of what things are supposed to be in society because that’s the way they’ve been in the past. So, if you keep chipping away at what alternatives you give people to experience, they’ll start to come along, I think it’s inevitable, but you can’t give up just because it doesn’t make change immediately. But I like the idea that you always want to give people alternatives to what is mainstreamly available.

Johanna Drucker Is there a danger—and here I’ll do my little provocative moment, okay—is there a danger in sort of fetishizing esoteric experience over mainstream experience? Is there a way that there are things that are within the mainstream that also are empowering? I think about the—you go to the LA Art Book Fair now and it’s fantastic how many people are involved and the kind of—now it’s a small percentage of the population, still, but many of the things that are being published or printed there speak in a direct voice, they are not esoteric particularly, they’re not part of a kind of avant-garde tradition, they’re much more of a kind of community based or alternative voice platform really wanting to speak directly about issues and ideas. So again, I’m esoteric of the esoteric and I’m with you Susan all the way that offering people an experience so that you can have experience in this life outside of the monoculture is crucial. But there is a kind of tendency to think, “Well if it’s difficult it must be important,” or, “It’s more transformative if it’s esoteric.” And I feel like that’s an assumption that maybe I feel some skepticism about.

Susan Sironi Well I think the idea was what the aim of the alternative is, is it only to provoke or is it really to engage? So that would be the distinction for me, yeah that’s about it. I don’t like provocation for provocation’s sake. That would be not worthy of the incredible expense to go, but no I can…

Marcia Reed Susan, though, it’s interesting because that what the Dada artists did, they just kind of wanted to shake things up and they did it to kind of make people readjust. So, I had a really hard time with Dada for a while because I couldn’t see, “Where is it going, what are they doing?” And then I realized, actually, it’s sort of like adolescent behavior, it just sort of is and then it allows you to move on in a way.

Johanna Drucker There’s a politics to Dada which was to question the sort of hegemony of rational action, which…

Marcia Reed Exactly.

Johanna Drucker Yes, exactly, which wasn’t acting rationally in the beginning of the First World War.

Marcia Reed Well, I think to show that there was a value to the irrational…

<overlapping conversation>

Johanna Drucker Exactly.

Marcia Reed …To make you think, hopefully, outside of the box. I think what’s nice about what artists’ books did for women or social activism was it gave them a way, and I think we talked about this a little bit, to put things out there. There could be zines. There could be broadsides. I like that openness of format that you think about, “Well what works? Is it better to make a box of things for someone to look at to consider as a kind of gift experience?” that’s a kind of a book as well. But we haven’t really talked about how format can work for your purposes, and I think that’s an interesting thing, to be very open about what the book can be, not just a rectangular bunch of paper or something like that, but to tailor the book for what you’re trying to get out there, what you want to have engaged with.

Johanna Drucker Yes, format—we’re going to run out of time in a minute for this part of the program, and I think I want to see what kind of questions our audience might have for you folks, but I wonder if we speak about format, again I think the book is an incredible cultural icon, it has so much authority as a form, right, and it plays religious roles, it plays ceremonial roles and this is across cultures, right, and across religions and across beliefs, whether it’s scrolls or codices or other kinds of documents, so the cultural authority of books is very real. But here we are in this digital era, so it’s like does the digital challenge the book? What I think over the long view is that instead it’s reinforcing our attachment to this form and to its authority and its capability, its incredible variety. What do you folks think? This is my last question to you in my moderator mode here. Does the cultural authority of the book continue, get reinforced, get lessened, get transformed in relationship to digital media?

Marcia Reed I totally agree with you Johanna. I was going to ask you what do you think. Yeah, I think books are very special to people and they have this intimate engagement, so I completely agree with you, I don’t think the book is going away, no, no, no.

Susan Sironi We said painting was dying too and yet we get a lot of painters here still, so it might transform, but I think it could become more precious. It’s easier to put things on digital, and I’ve seen some of your work Johanna with how you use the technology and digital things to help people gain understanding about what they’re reading, but I don’t think we’ll get away from the physicality of a book. There’s just too much beauty involved in the consideration that it takes to make one, so they’re here to stay.

Tia Blassingame I mean I’m excited about how artists’ books and book arts kind of brings in technology and adjusts with technology, I think similar to print making as well. So, I think in some form they’re definitely here to stay and hopefully in forms that we have yet to imagine.

Johanna Drucker Alexandra, I’m going to give you the last word on this because you were talking earlier about the haptic aspect of the book and yet how that didn’t define or limit a… but you should speak about whatever you like on this one.

“I think the haptic—the idea that we love the touch and smell of the ink, of the paper, how the binding, the cover, texture is so important.”

Alexandra Grant I think the haptic—the idea that we love the touch and smell of the ink, of the paper, how the binding, the cover, texture is so important. But I also think that we’re living in a culture where there is publishing and sort of editioning of things that are happening through social media, but they always are a return in a way, you know, that here are people on Instagram and they’re thinking in relation how is this text or this code or these emojis going to work in relation to this image. There are people publishing as NFTs and some of them are making windfalls and some people are exploring different ways of embedding information with these digital images. I think there is definitely a relationship to publishing that is happening even in technology. We didn’t even go into this, but the idea of the multiple and reproduction and the original and all these questions, I think the technology leads us back to the book, it takes us away from it, but we come back to it in part because, not to come back full circle, but because books still are those seeds, those plans, that site of investment into the most compact space of a whole world that we wish to see built.

Johanna Drucker Lovely. Okay, here’s a question for you. Could Tia, Susan and Alexandra talk about their process as artists who work with the book as form? So, this is a nice segue, actually, from what you all were just saying. So, what aesthetics and techniques do you use and why do you want to transmit with them? In other words, how do those choices about the format, the medium and technology, how do those factor into your convictions about the book? It’s really more to you as artists to talk about your processes.

Susan Sironi If I start a book that is very intricate, in order to cut through it, I have to understand it 100 percent, I have to know every page. So, if I want to engineer a collage-like element into it, I can scan it, I can do it in Photoshop, I can practice with multiple copies. So, if I choose a book, its physical form is really important to me and how I go about understanding sequences, where text and images go. That will determine on what books I select. So, for me it’s just kind of understanding of having done something to know what processes I want to use in the future.

Tia Blassingame I’m happy to pick up. So, for me each book is different of what it kind of wants to be and how I want you to—what your relationship would be to the book. So I have a piece, “Harvest,” that I wanted there to be some physical relationship and movement between you and the book and so having you have to move back and forth, so front and back and then kind of side to side with the book, so decisions around the size of the type—some of it is challenging to read, so you have to move in, but to turn the page, you have to move out. There’s a sound aspect, too, that plays off that as well, so I think each one is different. And I always try to build in something for myself that isn’t going to be apparent to the reader or anyone within the process. I really like process particularly because this subject matter can be very challenging, so I need a lot of time to process the subject matter in my decisions as well. So, I seem to be drawn to print making processes that are super drawn out to give me that time and space and even to have kind of like a sound aspect within that as well, so something like etching and that mark-making and so the rhythm of that mark making is kind of for me to sort of chill me out and let me kind of meditate on the subject matter. But I would say each project is very different and that’s primarily because each one has a different way that I’m looking for you to physically interact with the piece.

Alexandra Grant When I was a graduate student at the California College of the Arts in San Francisco, my arts education experience, I think like many young artists, was to be given an empty white box and then [was] sort of left to my own devices. And I had this question in my mind which was, “What will I care about in five years, ten years and twenty years and how can I figure out what that will be when no one is looking and when everybody’s looking?” And I sat in the studio and I really, I looked at the other students and I took the classes and what I realized that the thing I knew I would do that I had loved to do my entire life until graduate school was that I loved to read and that I wanted to imagine in that space of artistic practice is being a reader who then responded initially through painting and that has grown over the years, but to writers I admired. And it began with writers I didn’t know and then went on to be with writers with whom I’d collaborated. And then out of that grew the invitation to make artists’ books first for me and then the joy, the real joy, of working with other artists, right, and bringing my life experience to give the permission that I had been given to other artists and that incredible creativity that comes when you’re working with someone else. So, for me, I’m not sure if this is really answering the question, but it’s that how is reading, the dignity of the reader at the heart of the imagination. And often I’m just so touched by the idea that writing —it gets back to the biblical sense in the beginning was the word that the word is transformed when embodied. I often work with groups of people, and I do an exercise where I have everyone in the room draw a frog and then everyone has to show their frog and every frog is so different. So, when we think about like that if each one of us has a completely different frog inside then how are we even able to communicate in a sentence, like each word, if we embody it so differently? So, I guess it’s a complex and simple answer, that I keep returning to reading and that my source for any project comes from finding a process, finding materials, if there’s another person involved, finding the equal footing to be in exchange with that person around a passion for the written word and for the narrative, for the story.

Marcia Reed It’s funny, I love reading—I mean my name, we just spelled one letter is wrong— but I actually love the idea of combining visual reading with reading text and that is maybe one of my favorite things about artists’ books is that they put that together also with format, so you’re reading in a different way. But I guess because I am an art historian, I think visual reading is really important as well as text.

Johanna Drucker Yes, I think that’s really crucial, and, again, I think it’s one of the things that makes artists’ books somewhat problematic in terms of where they sit. It’s like, “Do they belong in the library?” or, “Do they belong in the museum?” or, “Do they belong in the gallery?” and if you put them in a case, you can’t read them. I would think as a curator Marcia, I’m also thinking about the dilemmas that you have when those people come to bring those books full of sand and <laughs> you’re like, “Well what happens when all the sand runs out, is it still the same book?”

<overlapping conversation>

Marcia Reed I was trying to figure out, Alexandra, which one it was because we actually have several, we have “Holton Rowers” and we have a bunch of them. <laughs> But that’s part of the thing that somehow you have to allow that to happen. We have James Lee Byar’s book which is just filled with sparkle confetti and the experience of that book is, “Oh my god, it’s all over me.” And how could we allow that to happen in the reading room?

Johanna Drucker Exactly. And then the books that self-destruct. Let’s see. The audience is interested in—well there’s a question about audience, how important is it to think about your audience when you’re making the work? It’s a fundamental artist author question, but do you all have thoughts on that?

Tia Blassingame Oh my god, I haven’t been teaching for a semester, so I’m off. This is going to be how my fall is going to be. I apologize. For my own work, I think about this a lot like my target audience and who that is and how are they going to approach the work, is it going to be too precious for them to even want to touch it and things like that. So, I think about this a lot, and I have multiple audiences that I’m trying to reach. But in the end maybe the audience is anybody and everybody because you never know who’s going to see your book as appealing or curious. I also think a lot about those different types of target audiences and how far they’ll go in the book. I want them to go all the way through and through that journey, but they’re probably not because there are works that deal with issues of race and that’s challenging and most people want to avoid those conversations, right? And so, if they only get two pages in and then hands off, I still feel like I’ve had some impact on them and that they can move away from that experience and still be having a conversation about the subject matter even if it’s just, “Oh, I interacted with this book and it was kind of weird,” I still think I’ve reached them in some manner.

Johanna Drucker Alexandra, you work as a publisher also, not just as an artist, and your relationship to books has involved a great deal of publishing decision-making, and I wonder if you think differently about audience when you’re thinking about publishing versus your own creative practice.

Alexandra Grant I mean audience is such an amorphous, it’s an amorphous word, I often find that the audience is defined—you only define it after you’ve found them, right, so <laughs> they’re the people who love what you do. You know, one thing I mentioned that we published “The Words of Others” for REDCAT for the Getty’s PST Los Angeles Latin America and for me that book was such an extraordinary work, it was a nine-hour play, it involved three years of translation and research to find the sources, there were 200 sources collaged into this sort of found work. And what was interesting about the book is that the show that Ruth Estevez-Gomez curated was around the artist’s book and the exhibition catalog had a publisher, but the actual artist’s book that Leon Ferrari had—his family had allowed the team to translate into English for the first time didn’t have a publisher. And so, I thought, this question of audience came up for me then. It was like, “So there’s an audience for the secondary materials around this artist’s book, but there’s no publisher available for the artist’s book itself.” And we were able in our first year as a publishing house to step in to fill that void. And then it became up to us to find who the audience for the primary source was. And so, I found that a fascinating question around audience and distribution and publishing at a commercial level and then also this void, right? Someone said earlier that artists’ book are almost like—where do they fit? I love this question, “What are they, is it like a verb or a noun?” and none of us know and yet it’s everything, it should be in a library, it should be in someone’s hand, it should be in a Plexiglass. And so that question of our particular concern for this artist’s book is that it’s better almost not to know who the audience is, it’s better not to plan it out but that there are other likeminded people who one will identify. And that for me, the learning around “The Words of Others” really made that clear that a mainstream publisher wouldn’t want to get involved because of the fear of not knowing who the audience was. And so, the fearlessness of being an artists’ book publisher involved, “I don’t know, but I can’t wait to meet them.” <laughs> And I hope that we’ll be able to not only be good family to this book, but provide a family of other books that are bit orphaned—we take on a lot of orphaned books at X Artists’ Books, where someone will say, “Oh, I’ve been working on this for so many years and it’s been rejected 17,000 times.” And we didn’t know, we did a book with George Herms and Diane di Prima, it was the last or second to last book before Diane passed away and George said to me one day, “You know, we waited for you for 50 years,” and I said, “Well I wasn’t born.” But that idea that often with these very heterogeneous projects that don’t fit any neat hole, that we don’t know who the audience is. And actually, I feel wonderfully comfortable with it to be delighted when I meet them.

Johanna Drucker I think what you’re saying also resonates a bit with what Marcia was saying earlier about books have long lives. They live longer than we do, and they find other audiences, completely unexpected audiences, and get received again and again in completely different cultural moments and historical frameworks. Susan, I want to give you a chance if you had something you wanted to say about audience for your work because, again, it’s got a somewhat different trajectory.

Susan Sironi Well the first impression was that if I cut a book that’s very popular like say, “Alice in Wonderland” with the original illustrations, people who are familiar with that book, if I cut it up, they’re either going to love it or hate it because they’re going to feel like I’ve either trespassed or I have now enhanced—or they love the illustrations. So, I know that if I put something recognizable out, there’s an audience, but I don’t know how it will respond. So, I have to just kind of keep turning inward and say, “What do I need to say?” My books are going to be pretty selectively viewed through galleries and exhibitions, so I don’t see—my work doesn’t translate well online or in any other kind of form, so my audience is going to be someone who goes to see them, they will never come to them. So, it kind of puts the burden back on me, on making sure that my message is personal enough, but at the same time doesn’t alienate by being too personal.

Johanna Drucker Your works are unique works, so they’re not editioned in the same way, so they again circulate differently than editioned works. Marcia, did you have anything you wanted to say on this? And then I’m going to pull the questions together towards a kind of wrap up here.

Marcia Reed Not really because I think unique books have their own way of being. We have a wonderful scrapbook that I’m not even sure how much he wanted to have this scrapbook, personal scrapbook by Benjamin Patterson who is an artist, musician, composer, but it came to Jean Brown in his archives, so he did know that it was passing from his hands out into the world. It’s just this amazing collaged children’s ABC book that then he put together in another way. And it’s just an extraordinary work, it’s a unique work. And so, I think you do what you do, the edition or the unique work according to your own practice and then luckily because of digital technology and the ability to reproduce things, those things now can go out there in a way that maybe it’s not the real thing, but it is going out into the world, the images, the ideas will.

Johanna Drucker No, exactly. I think each project offers different kinds of challenges and opportunities, and Susan was just saying, it’s like her work does not remediate well. You need the experience of it in person to really appreciate what the spatial, scale, sculptural qualities are. But then there are works that can be remediated. Yeah, it’s a different experience, but it’s still available. And to kind of wrap up here, I mean we could go on, there’s many topics more to talk about, but I don’t want to wear you guys out, and I think we don’t want to test the patience of our audience too long. But the question of has the pandemic introduced changes in our expectations, in our practices, do we think differently about the making of books now? I mean Tia, you talked about the teaching experience, and I had the same, my students did fantastic things, but there’s also the frustration of not being able to go to the library, not having access to special collections, only being able to see things that are online. Does it make us think differently than we did two years ago about what we’re doing? Does it just make us want to go back to where we were? Will we come out of this experience with a different sense of what our purpose is and what our practices are than we had going in? What do you think?

Tia Blassingame I mean hopefully we don’t go back. I feel like the studio classes that I taught, I feel like there were students that would have struggled more in an in-person class environment but were really able to shine and make really strong work and really kind of connect within that work in ways that I don’t believe they would have if we had been in person. I think also just access to learning new techniques has kind of shifted. You don’t have to just have enough money to fly off somewhere to take a weekend workshop or a weeklong workshop, you can just kind of Zoom in if you have Wi-Fi, et cetera, things like sliding scale for workshops. So, I think there are a lot of aspects of our experience during the pandemic that hopefully will remain in some manner, I would hate for us to go back. I think for my own practice, just trying to really focus on enjoying the processes and the process of making which I think maybe I had moved away from just with the pressure of kind of increasing my edition size and trying to get work done, but really trying to focus on just enjoying that process of making.

Johanna Drucker Yes.

Susan Sironi I think I learned a little bit more about not taking things for granted. Along with the travel and being able to socialize, how do I spend my time, how do I kind of take on the idea that what happens if the pandemic comes back again, do we continue to make things that we think, “well they can be changed later,” or do we start to focus on really making the best things that we can now knowing that there might not be a second chance, we could get shut down again. I’m a little more appreciative of my time now. I seem to see it a little more preciously. And so, if I do see someone or go out to a show, I think I’m paying attention a lot more than I had a year ago. I hope it doesn’t wear off. I hope it retains a kind of sense of importance that time is valuable.