Memory, Feeling, Energy: An Interview with Lisa Diane Wedgeworth by Jordana Moore Saggese

“I’m definitely more and more convinced that black

is actually the beginning of everything,

which the art concept is not.

Black gets rid of the historical definition.

Black is a state of being blind and more aware.

Black is a oneness with birth.

Black is within totality, the oneness of all.

Black – is the expansion of consciousness in all directions.”

– Aldo Tambelini

LISA DIANE Wedgeworth is an interdisciplinary artist whose large-scale abstract paintings are informed by memory and employ energetic mark-making to interpret psychological and emotional energies. She is a recipient of the 2020 COLA Individual Artist Fellowship and is an adjunct lecturer at Los Angeles City College, Glendale Community College, and UCLA. Wedgeworth exhibited emerging artists in her studio-based project space PS 2920 between 2015 – 2016 and recently launched the public platform, Conversations About Abstraction to share the voices of abstract artists historically excluded from the Western canon. JORDANA Moore Saggese is an Associate Professor of American Art at the University of Maryland, College Park and Editor-in-Chief of the College Art Association’s Art Journal. Saggese’s work focuses on modern and contemporary American art with an emphasis on the expressions and theorizations of blackness. Her newest book The Jean-Michel Basquiat Reader: Writings, Interviews, and Critical Responses will be published in March 2021 by the University of California Press.

JORDANA Can you tell me about your background, growing up? When did you know you wanted to become an artist?

LISA DIANE Very early. But I don’t remember using the word “artist.” In my childhood, I was very fortunate to have a mother who was creative. Our home was very nurturing for creativity. My mother worked for an advertising company or something of that nature, and I recall her having a party where she laid a billboard of curvaceous bodies in jeans, it was a Ditto’s advertisement, on the floor and everybody danced on that, danced on bodies in jeans. My mother redrew comic strips, enlarging and framing them and hung them in our breakfast nook, our home was a really nurturing environment. All of her friends were creative women, photographers and chefs, and batik artists, women creating in a variety of ways. We were raised in a very creative environment, my mother took us to art classes and to museums. I have very early memories of making art and being inspired to make art in school. I have a very vivid memory of being in elementary school, at Wilton Place Elementary School, and instead of going outside to play during recess, I was indoors, making a dollhouse out of a cardboard box. Somewhere, in my little mind, when I saw this box I wanted to do it and told one of the teachers, and they supported me. I guess they must have given me a pencil, ruler, scissors because I remember cutting up a column and bending it and making stairs for the second story, and gluing. I enjoyed the art classes and am grateful for those early teachers who introduced me to creative writing at Fletcher Drive and Balboa Elementary school. My gravitation to art was always there, I was always attracted to art. But I didn’t know that word, “artist.” I don’t recall knowing that word, that’s just what I was.

In high school, I didn’t always feel confident because I had to take an art class where we had to draw. And I could not draw photo-realistically. If you tell somebody you’re an artist, they’re always like, “draw this.” And that’s the proof that you’re an artist. Well, I didn’t understand at that time that you could be a photographer or a ceramicist or an abstract painter or a dancer. Because I couldn’t draw, I believed art was not for me, until I took a photography class, and I thought, “ohhhh.” I really resonated with photography, and it helped me express myself. Then, I went to Howard University for a year and took photography there, and interior design, and wanted to go into architecture. So, there’s always been this creative path that I’ve traveled. It wasn’t until I was in my 20s, living on my own, practicing photography, that I realized I had become an artist, and that that was just my life. And then, that word started being used. I don’t recall exactly when, but I claimed being an artist.

“If you tell somebody you’re an artist, they’re always like, “draw this.” And that’s the proof that you’re an artist. Well, I didn’t understand at that time that you could be a photographer or a ceramicist or an abstract painter or a dancer.”

JORDANA It’s so interesting to think about this idea of claiming your identity as an artist. I’m especially touched by the story of high school and drawing classes. In so many ways, I often wish that people would intervene, just go into all the high school art classes and say, “Actually, you can be an artist and not do this one thing.”

LISA DIANE Right, or understand that art is a muscle, that you can learn to draw. There are people who have very natural skills, from an early age. Or, you know, those that, even once they’re trained, draw in a much more realistic way than someone else. But we can all learn to draw, we can all learn to see, you know? And if you do it every day, then it gets stronger and better. I didn’t understand that.

JORDANA Yeah, so you took classes in photography. What was your training like, formally or informally? It sounds as if you had a little bit of both.

LISA DIANE So I took photography in high school. When I went to Howard University, I was accepted into the school of Human Ecology but I don’t think it exists anymore, to study interior design. I liked interior design, but when I learned that, at that time, interior designers could not remove interior walls, that was something only an architect could do, I wanted to go into the school of architecture. I started hanging out there, meeting students, taking architecture classes. And then, I saw that all the architecture students lived in the building and never left, and I was like, I think this is too intense. I wasn’t trying to do all that. And then, I started dating this guy, and I don’t remember if he had a camera– somehow I got a camera, I started taking photographs, and I thought, “I need to be in the school of fine arts,” and started taking photographs under Professor Kennedy. And he was married to Deborah Willis, the photography historian. And that’s when I was just like, this is it, you know? I knew photography was my medium. So, I was trained in photography at Howard, left Howard, came back to California. I wanted to go to an art school so I left DC. But I didn’t go to an art school. I did photography on my own. I took myself to galleries, did a lot of self-learning and training. I had a mentor, Willy Middlebrook. I had a child and started working at Fox broadcasting as a coordinator in the photo publicity department.

I remember reading Julia Cameron’s “The Artist’s Way,” and, somewhere in a chapter, she talks about people who are creative or artists, but they’re not pursuing that path, often finding themselves in positions where they still surround themselves by the things that they love. And I didn’t want to only surround myself by it, I wanted to be doing it. So, while I was there, I took a two-week vacation and started classes at Cal State LA to get my undergraduate degree, and then came back after the two weeks and said, I’m in school, and quit my job. And so, I trained at Cal State LA in photography. After that, I was working in photography and teaching. I was never a commercial photographer but making photographs as an artist. I had friends who were artists, but I didn’t feel like I was a part of an art world, you know? I’d show my work here and there. And then, while I was teaching, I was teaching art to developmentally disabled people, and I met Varnette Honeywood, who was an artist. Her work was shown on “The Cosby Show” and in other places, I don’t know if you remember, I don’t know how old your kids are, they might be too young. There used to be a show called “Little Bill” that both my daughter and I loved, Varnette’s work inspired the art for the Little Bill Series.

When I met Varnette Honeywood, we started hanging out, she became a mentor, and she encouraged me to go to graduate school. She said, “you’re an artist, just go and get that degree. Just get that piece of paper, because if you ever want to teach, you have that. Nobody can take that away from you.” She wrote my letter of recommendation, and I went back to Cal State LA for grad school. I wanted to go to New York, Paris, or somewhere, but my daughter was in high school, and I didn’t want to uproot her. So I said, I’m going to go to Cal State LA, to get my degree. At the time, I believe that it was not simply where I go, it’s about who I am and what I want to get from that. I do think it’s where you go because there are relationships that exist. If I had maybe taken another year and really worked on a portfolio, done some research about where I wanted to go… Because we do know that there are pipelines into the art world, and relationships that exist, you know? What I do like about it, and what I learned is that you have to have a very entrepreneurial spirit, because everything is just not given to you. You’ve got to find and fight for studios, and we didn’t have visiting artists come. So there’s a lot that you had to do on your own. I learned a lot about myself in graduate school, and I applied for the studio art major, not photography, only because I wanted to have a studio. I knew that if I went as a photography major I’d have a dark room, but I wouldn’t have the studio, because I knew that I wanted to explore other media. So, I was working in photography making video, but I also started painting. I started working in three-dimensional sculpture and I started making those large, black paintings, which have continued today.

“It wasn’t until I was in my 20s, living on my own, practicing photography, that I realized I had become an artist, and that that was just my life.”

JORDANA That’s so fascinating. I’m always interested in talking to artists and thinking about what they made and did before they knew that they were making things. So that grad school studio experimental space sounds like a place where you really landed on this format that is still very powerful today. I wanted to hear a little bit more about your influences. You’ve mentioned some of your mentors and how they guided you along this path over a period of years. I know that you’ve mentioned, in other interviews, that you really felt the works of Lezley Saar or Suzanne Jackson were really important to you. So, I’m wondering, what is it about their work that speaks to you?

LISA DIANE Well, I’ll tell you, I didn’t know much about art when I was taking myself on these trips. I just knew I wanted to be an artist. I was creative. So I would take myself, when I was in my early-20s, on my own gallery trips. I’d go to La Brea and I’d walk up and down La Brea. And I’d go into galleries. And when I first saw Lezley Saar’s work, I had no idea about the Saar family. I don’t recall seeing Black people in art, because I walked into this gallery, and I saw this painting, and read the title, and it said, Octoroon or Quadroon. I knew what that term meant, and I think it was the hair. I was like, this is a Black person. I was looking around, and when I read the title, I was like, this has to be a Black artist. I was looking around and asking about this and wondering, is anyone as excited as I am? Why is no one responding? I think this is a Black woman who made this, you know? I didn’t ever see Black artists. So, that was the only time I had seen a Lezley Saar painting, which was inspiring to me, like… “Wow, there’s a Black woman who has artwork in a gallery, so this is possible.” And then, I came across the work of Suzanne Jackson. I love her touch the light application of acrylic as watercolor, the faintness, the way it flows. I think what all of those works did for me… one thing that I haven’t mentioned is… Well, first of all, Lezley Saar, seeing her work helped me understand that I could be in a gallery, that this was possible. I love Suzanne Jackson’s painting style. But it was really the work of Lorna Simpson and Carrie Mae Weems, especially Lorna Simpson, that gave me permission, as a photographer, to include text in my writing. Those early creative writing classes from elementary school unleashed a love for writing combined with my appreciation for great storytelling modeled by my parents. Simpson’s text-based photography work made me think, I can combine these? I didn’t know I could do this! When we’re learning, we have these very rigid ways of being, right? And when I teach my 2D class, I get that resistance from what the students perceived to be rigid restrictions.

But what they don’t understand is that you have to have limitations in the form of assignments or projects so you learn the foundation, once you learn these things, then you can break the rules later. You don’t realize that you’re allowed to break the rules when you’re an artist, and you can do really anything that you want. It was really Lorna Simpson. At this time Lorna Simpson and Carrie Mae Weems were doing photography. And I was still a photographer when I was going to the galleries and looking at paintings. So, when I saw Lezley Saar’s work, I wasn’t painting. I was in photography. But it was just exciting to know that there was a Black woman in a gallery. I think all of those people gave me permission, told me that I could exist in these spaces and that I could make work that didn’t look like traditional painting, that I could have my own, unique style.

JORDANA Yeah, I think there’s a lot of freedom in that, right? I’m continually interested in Los Angeles and the art world there– I don’t know if you’re familiar with Kellie Jones’s book, South of Pico,” that talks about a Black art scene in Los Angeles that has been just completely overlooked. And I think it’s very striking to hear you talk about being in those gallery spaces and seeing Black artists and realizing that they are Black and that they are successful, and that really shifting a worldview for you. In the art world today, we see this intense interest in Blackness and in Black artists, what do you make of that, in comparison to the time when you were coming up? What do you think it’s like for an artist coming up now, in this new world?

LISA DIANE Well, first of all, I think that it’s amazing. I think that, as a young person, you see a lot of yourself. So, this is definitely doable, right? We are here. I think it’s fabulous, it’s wonderful. I think that we should also hold ourselves to some standards, that you still do the work, you still understand your materials. I try not to go on so much anymore and try to wean myself from social media, but I have seen a lot of very young artists on Instagram who are making work, and it looks exactly like Jean-Michel Basquiat, and they profess to be original. And I think, well, no, actually, someone already did that. I think,” keep making, find your voice.” And that maybe if you did, even on your own, study color, you’d understand complementary colors. You’d understand how, maybe, to make this stronger. You’d understand more. I think the interest, the access, is fabulous.

JORDANA Yeah, I think that’s exactly right.

LISA DIANE And learn how to create your own style.

JORDANA Mm-hm. Yeah, I always tell my art students, you have to know who’s in this conversation. You have to know who came before you, before you figure out what you’re going to say.” I think that’s so critical.

Often, when I’m teaching, especially when I’m thinking about abstraction, I’m teaching the work of Raymond Saunders, for example, another California artist, who famously more than 45 years ago declared his position against people who place the burden of politics on Black expression. He’s someone who chose to pursue abstraction as a way out of figuration.

LISA DIANE You know, someone just told me about Raymond Saunders. I am not familiar with him, I should look him up.

JORDANA I will send you his essay “Black is a Color” from 1967. He’s a really important figure in this moment of the late-1960s, early 1970s, where he’s explicitly choosing to pursue abstraction as a way to not only escape figuration but as a way to escape the explicitly social function of art. Feeling that there was this tension between the binary of the social versus the aesthetic. Have you ever felt the pressure of that binary —of choosing between the social and the aesthetic? And has that changed over time?

LISA DIANE And the social being… what? Like a responsibility?

JORDANA Yeah.

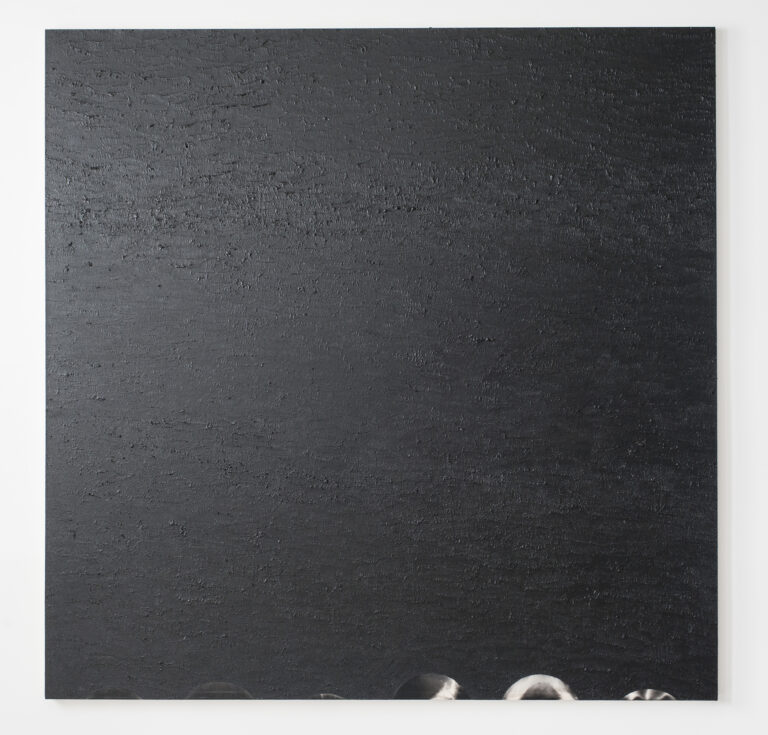

LISA DIANE I would say, I don’t feel pressure to choose. I’m making work that is resonating with me. The work may be a performance, video, or painting which I am currently prioritizing in my practice. I love painting and abstraction, it is the best language I can use to express what I see, feel, and want to say without using words. My paintings are very much about drawing and painting. They are about the painting itself, but there’s so much more because it’s an extension of me. I think, because I have so much to say, that my paintings are always going to have this balance between social and aesthetic. I’m interpreting and understanding social as having content and meaning politically, about my status, the world… But there’s a balance. At least this is how I’m interpreting it. At this time, I can’t separate that. I have never felt pressured to do that. I’ve never felt pressure to choose because I believe the social and the aesthetic can coexist within a work. Abstraction allows for a coexistence, it allows you to boldly address, confront, analyze and explore ideas using a language the viewer has to make time to discover and understand. I love that about abstraction. Many people discover and understand the work with an emotional response. I have a show coming up, and I did submit writing about the work. And here I am talking about the work. When viewing my work, I want people to go into the space and look, engage and have an experience with it. I’d love for most people to maybe go in and not to read anything. Go in and think about what the work is saying to you? How are you resonating with this? The painting is also so much about that, you know, the aesthetics.

“I’d love for most people to maybe go in and not read anything. Go in and think about what is it saying to you? How are you resonating with this? The painting is also so much about the aesthetics.”

JORDANA Yeah, that’s really fascinating. I’m curious about your choice to use different types of tools, right, to sort of inscribe onto the canvas. What motivates those decisions?

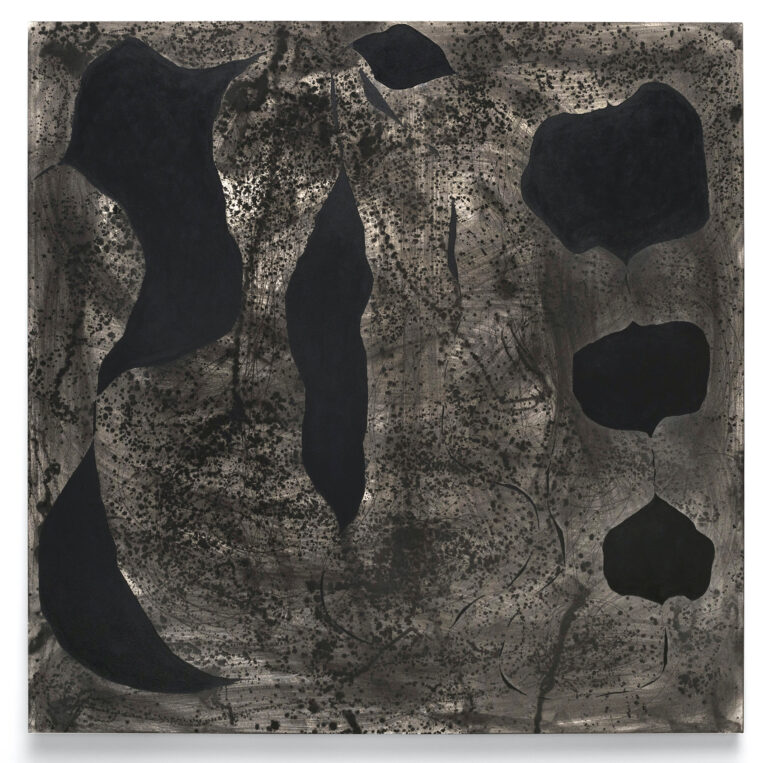

LISA DIANE It comes down to the types of marks that I want to make in that moment as a response to what I am feeling as I am making the work. There is a part of the process that is very organic as it is not planned, this is where the mark-making takes place, I have these tools I have configured from a variety of objects such as spatulas, toothbrushes, and other objects I use regularly next to me, and depending on the type of marks that I, in the moment, want to make, then I have this access. But it’s really not even simply about the tools, it’s how I make the marks that become really important. It is how my body moves as I am making marks. And literally, sometimes I’m standing in front of the canvas, breathing with the work, allowing myself to really feel what this painting is about, and just start making these marks.

JORDANA Yeah, this idea of process seems to be very important.

LISA DIANE Yes…

JORDANA You’ve spoken before of your abstract work of being very connected to your own body and your own biography. And I think that’s something that many viewers of an abstract painting may not immediately understand, right? Can you talk about how your autobiography impacts your painting process?

“I feel, on some level, that the paintings are also like pages from my diary.”

LISA DIANE I’m really excited when I make my paintings, and I want to reinterpret memory, feelings, and the energy of these experiences I am recalling in the paintings. I feel, on some level, that the paintings are also like pages from my diary. I don’t really write in a diary journal anymore. I used to a lot, but these are ways for me to share memories. And since they are abstract, I’m interested in the feeling of these memories. What I now understand is that I am making space for myself in my world that is transitioning from one where my purpose was so ingrained in being a mother and the realization and acceptance of being a woman who is in her early 50s. I feel a bit invisible, so making these paintings that take up literal space and whose content explores my body and conjured energies associated with these narratives are my diary entries. These paintings become alternatives to conversations or extensions of the journal writing. I think you asked me something, but am I answering it? I kind of forgot your question.

JORDANA No, I think that’s exactly right. I was interested in how biography filters into abstraction.

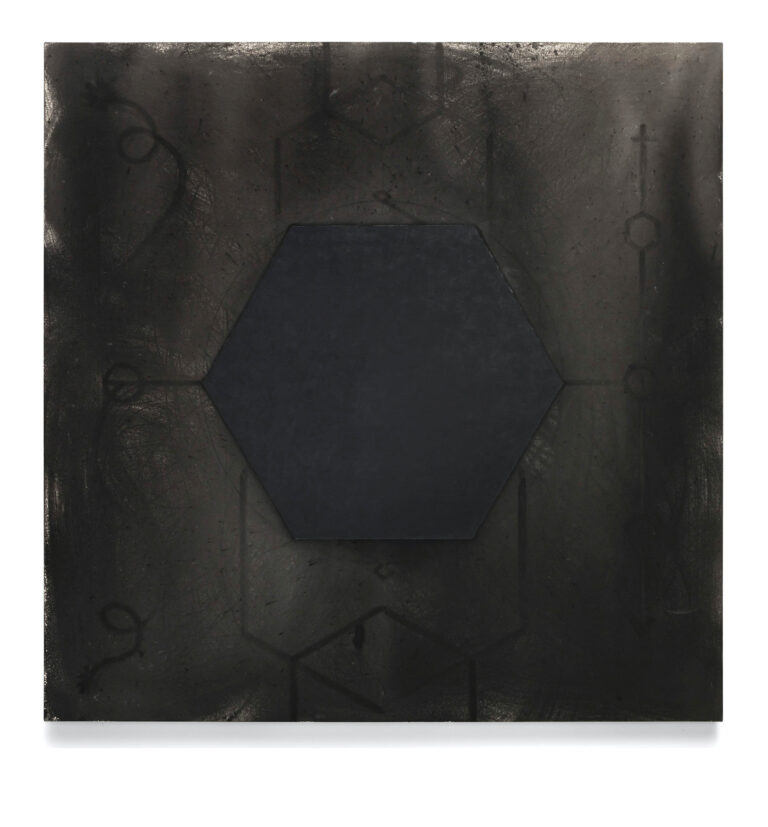

LISA DIANE I had someone come to my studio and say, they had collectors that were really interested in buying work that had Black bodies in it. And I said, well, this painting does have that quite literally. There’s a black triangle, right? The triangle is a body. It’s an element. It’s me. It’s just abstract, you know? This is not representational work, but my Black body is in it, and the painting is literally my size, my height, and my width when I stretch out my arms. So, the painting is a representation of my body. It’s here. But if somebody cannot see that then this is not the work for them. So, I’m deconstructing these ideas. I’m reducing these formal shapes of figuration into these geometric shapes, right? So, it’s here, it’s just taking a different form.

JORDANA My initial reaction to hearing that is, well, it’s here but it’s not here. Right?

LISA DIANE It’s only not there because it’s not taking the form that you’re used to. But it’s there.

JORDANA Yeah. In that unconventional form of the body, is there any form of resistance in that choice? Or is there any form of challenge in that? Lorna Simpson is a great example of what I’m thinking of here. In the series Guarded Conditions, she denies access to the Black woman’s body, right, and shows us just the backs. That person is no longer subject to our gaze. And so, I’m wondering, do you see an element of that resistance [in your own work], that pushing back against a history of …

LISA DIANE It’s funny, I don’t know if I see it as a resistance, I see it more as an invitation. Come and see the world the way I see it. You don’t have to be limited to having evidence that– you don’t have to– why do you need proof? It’s very performative, right? I have to prove my Blackness because I have to throw in slang words or walk a certain way or prove that I eat this food. I should be able to show up in the form, with the experiences that I have, and still be a Black person. So, I’m inviting you to come and see my life experience. I’m inviting you to see the way I see the world. I’m inviting you to engage with me and my body in this non-traditional form. It’s definitely an invitation, I think, more than a resistance.

“I’m inviting you to engage with me and my body in this non-traditional form. It’s definitely an invitation, I think, more than a resistance.”

JORDANA Can you tell me a little bit about this move to performance? When does that happen for you? When do you begin performing?

LISA DIANE Well, first of all, the making of these paintings is very performative, it takes a lot out of me, physically. I was having this desire and well, I was introduced to acting as a child. There used to be a place here called the Ebony Showcase Theatre on Washington, and I took acting classes there. My acting coach was Marilyn Coleman. She played Bookman’s wife, Violet, on “Good Times” and she was a wonderful woman. I always wanted to act. I took acting in high school. I loved performing. I was starting to feel this desire, around 2015, 2016, I think even maybe before that, to do performance art. I was really attracted to it. So when I earned my MFA in 2014, I rented a storefront studio. I have two rooms and I used all of the studio, but the front room was also going to be an exhibition space. I primarily was interested in performance. So, the first performance we had there was Samplista!, which is Colin and Becky Stafford– I went to grad school with Colin and invited them to perform in that space. We had this large picture window in front, and I’d have the lights on, and we’d have performances at nights, people could drive by or sit out or stand out and watch these performances that were going on indoors. So, I was really starting to feel this desire to perform. I remember saying to a friend that I wanted to perform. I went to Janet E. Dandridge’s thesis exhibition at Otis where she wore a dress she designed that had the faces of the Black women who were killed by the… I can’t think of his name now, of the serial killer in Los Angeles who killed over a dozen Black women [Lonnie Franklin, Jr.]?

JORDANA Oh, I don’t know.

LISA DIANE There was a documentary about him. I can’t recall his name. But she had their faces screen-printed on the dress, and she was standing in the middle of this space. And I don’t remember if she invited people or not, but I just went and engaged with her in the space, and other people started coming as well. I was feeling this pull, wanting to do performance. In 2017, it was on Valentine’s Day, I did a performance– it was called “Sister Wedgeworth’s Love Letters for Everyday Folk,” and I sat on the corner of La Brea and Rodeo, this was before it was changed to Obama, and I would write love letters for anybody who walked by. That was my first performance. And then, I was invited to perform at Williams College, and I did a performance there, called “Mary Louise’s Beauty Regimen for Black Girls with Melanated Gums,” it was about my grandmother, who was very fair-skinned, and I did a performance where I scrubbed my feet, knees, elbows, and my gums, with everyday household materials, because she had talked about doing this to make our knees, our elbows, and our gums lighter. And my gums bled, and I had my mother record her voice, saying these alarming statements that my grandmother would say. And then, E. Patrick Johnson who I met at Williams College, we were on a panel together, invited me to perform at Northwestern. I did a performance there called “Four,” where I made four confessions, prepared for four dates, and had a four-course meal with four different people that I dated from the audience during this performance. I make paintings and I have made videos. The performances are really manifestations of all the same work. I’m doing the same thing, they just have to take different form. So, I’m talking about being a single, Black woman in my painting, right? In the curse-breaking painting, “Hex, Be Gone,” I’m talking about the same experience in “Four”. Performing and sharing these confessions or observations of my life, while I date four people from the audience. They’re addressing the same thing, they just have to come out in different ways. I see them in different ways, and I need to express them in these different ways. It’s all the same work, but each manifestation delves a bit deeper. I had a class when I was in grad school, where a professor asked us to compile all of the previous work that we had made and to identify an overarching theme. When I started looking at all this work, I was doing street photography, photographing street altars, all these things, it all started to make sense, that they all took these different forms, but they were all necessary related parts.

JORDANA That’s really wonderful. Perfect summary. Before we conclude, I would love to know what you’re working on now, and, in particular, what’s the most ambitious thing you have in your mind? Is there any large-scale project that you would really love to realize, but just seems too vast?

LISA DIANE Right now, the paintings that are showing at Band of Vices were made in 2020 when I was awarded the COLA fellowship. I made those paintings, but the pandemic hit and I wasn’t able to continue the vision that I had. I’m continuing some of those paintings. I’m expanding on a painting that I made in 2016 called “Sane Sister, Schizo Sister”. It’s a painting with these two circles in the middle. One represents me, one represents my sister, one of us is sane, one of us is schizophrenic. They look exactly the same. We can’t tell them apart. Raised in the same environment. So, I’m continuing that work with those circles changing shape as our life experiences occur. But the most ambitious… that’s a really fabulous question. So much in the present, right now. What is my most ambitious thing? That’s a hard question. I don’t know. It was funny, I was in the studio the other day, and I was thinking about some conversations that I’ve had with artists whose careers are really moving forward, and they are friends who are at different places in their careers. One frustration someone had was about a review written maybe after a year that they were really on the scene, and it said that the work was not changing. And my artist friend’s response to that, in our conversation, was, “well, it’s only been a year, and there are things that I still need to say.” So, you know, let the work unfold and evolve organically. Or someone making work, and then, all of a sudden, they start making this really gigantic work, which is great for them. I was in the studio thinking that I like the size of my paintings at this time. They’re six feet by six feet. And I have to be honest, I don’t know, yet, what that biggest ambition would be. I’d love to be in the Venice Biennale one day. I think it’s just maybe a place. I’d love to be invited to that, one day, you know? I’d love to have a retrospective at the Whitney or MOMA or an institution like those. But I think those are goals, places where I eventually want to end up. But, for the work, I think, honestly, I’m just at a place right now where I want it to evolve naturally. Someone came to the studio once who asked, well, how big will you go? Will you ever do a gigantic piece? And I just said, well, maybe, but I don’t want it to be gigantic just to be gigantic. I want the size to have meaning, I want it to be purposeful. And right now, these six-foot by six-foot paintings are just where they need to be. They are my size. They represent me in the gallery, or in your home, or wherever you take them. And I believe that they will possibly become larger in scale, but I think they’ll know when. I will know when that is supposed to happen. My biggest ambitions relate to where I want to go as an artist.

❧

This is a transcript from a phone interview between Lisa Diane Wedgeworth & Jordana Moore Saggese that took place on April 26, 2021, at 11:00 am ET.

The transcription has been edited for clarity and length.

This project is supported in part by The University of Maryland Art Gallery.

Thank you to Lisa Patricia Ortega-Miranda, Jordana Moore Saggese, Kim Schoenstadt and Diane Wedgeworth for the interview and the editing.