The Immortality of the Crab: A Conversation with Marta Pérez García and Juan Carlos Quintero Herencia

The wind crab,

the hurricane

is not powerful

the hurricane is an exorbitant body,

air crab,

terminal crab

unfurled on his route,

sunset of landscapes.

Juan Carlos Quintero Herencia,

“Fracaso del ojo” de El cuerpo del milagro

(Bokeh, 2016)

MARTA Pérez-García is originally from Arecibo (PR), she was trained as a printmaker at the Tyler School of Arts – Temple University (MFA). Ms. Perez-Garcia is recognized in Puerto Rico for her color woodcuts where she won a number of awards such as the grand prize at the XIII San Juan Biennial of Latin American and Caribbean Print in 2001, and where she exhibits in museums on a regular basis. JUAN CARLOS Quintero-Herencia is a Professor of Caribbean and Latin American Literature at the University of Maryland. His most recent publications include La máquina de la salsa: Tránsitos del sabor (2005), and La hoja de mar (:) Efecto archipiélago I (2016). As a poet he is the author of El hilo para el marisco/Cuaderno de los envíos (2002), Pen Club of Puerto Rico Poetry Prize, La caja negra (1996), Libro del sigiloso (2012) and El cuerpo del milagro (2016). This conversation was moderated by PATRICIA Ortega-Miranda, a PhD student at the University of Maryland and curatorial intern at Now Be Here. To watch the recorded conversation on YouTube click: HERE

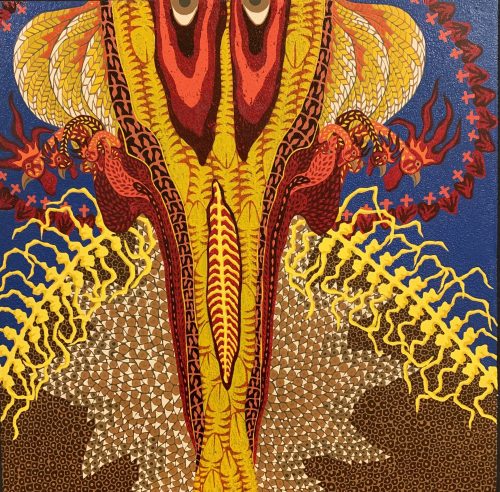

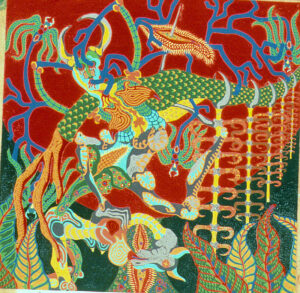

PATRICIA What motivates this conversation is an art piece that brings together many of the characteristic elements of Marta Pérez García’s work and is entitled The Immortality of the Crab. First, it alludes to the issue of violence against women, which Marta addresses in a very unique way, through a mixture of visual elements full of details and subtleties. It also addresses themes such as the relationship between life and death, sexuality, the body as a battlefield, religion, nature, and myths. In this work, we also see something that connects her engravings and installations and is the arrangement or assembly of panels; compositions that incorporate architectural or even sculptural elements. We could consider this work a mural insofar as it thinks about space in its specificity and through spatial movement. One of her classic anthropomorphic figures appears here, enfolding an imaginary of animals that resonate with various mythologies. Since these iconographic and symbolic elements are present in literature, history and popular culture, we invited Professor Juan Carlos Quintero to dwell on the figure of the crab, since he explores a large part of the Caribbean bestiary through his critical work and his poetry.

Genesis and Woodcut

PATRICIA Before getting into the matter of crustaceans, we would like Marta to tell us how this work came about and what place it occupies within her artistic trajectory.

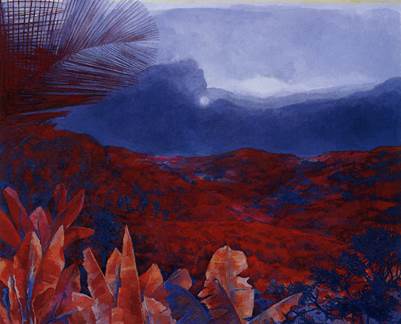

MARTA When I think about this piece, it brings back so many memories and I remember the reasons why I did it. I created it in 2014 for an art festival in Puerto Rico called La Campechada, which was a celebration of and a dedication to the work of Doña Myrna Báez, the first living female artist to receive this tribute. In 2013 my dear sister Marvette died, and since then I had not worked on my art. They called me to participate in the festival and create a piece that would talk about Doña Myrna, or that was inspired by one of her works. There is one in particular that I love, and it’s called The Red Plantains. It is quite great in color and design, and it has a wonderful haze. Recently I was talking to Juan Carlos about this painting, and I was telling him how I felt this silence that emanates from the piece, something like an incredible loneliness. Doña Myrna made some very beautiful landscapes of Puerto Rico. One of the main things I learned from her, was to know where I come from and to fight for who I am. And when I saw this mist and the mountains on the horizon what I saw was a dead female body. That is what inspired this work. I was mourning, affected by the death of my sister, and feeling lonely, so I decided to use my own iconography but inspired by the image in The Red Plantains. It’s interesting because Doña Myrna used to say that my pieces look like Mexican novels: you can make many out of just one. From there came the idea of fragmenting the image into panels and recreating the idea that in one image there are several stories. Also, I was feeling so broken, broken inside. In this work, I tried to reflect that, like an echo of the situation in Puerto Rico, of our colonial legacy, of all those fractures.

“It’s interesting because Doña Myrna used to say that my pieces look like Mexican novels, you can make many out of just one.”

PATRICIA Marta, that work by Doña Myrna, when was it painted?

MARTA She painted it in 1991, it is an oil on canvas. Doña Myrna did many landscapes and portraits. But for me, this work is a landscape and a portrait at the same time. Now that I think about it, I never discussed this with Dona Myrna. I would have liked to tell her what I saw or asked her if that was indeed a body lying down. But I never asked her.

PATRICIA Your piece was then on display in Puerto Rico at that time.

MARTA Yes, in La Campechada in 2014. This piece was created at a time when my experience as a student of Doña Myrna, my admiration for her, and the situation I was going through intersected. It encompassed the presence of two women who had been so important in my life, and with such force, at the moment when I had lost one and, in a way, the other was disappearing little by little.

PATRICIA Thank you for sharing such personal experiences that help us better understand your work as an artist. It is important to note that you were inspired by an oil on canvas to create a woodcut and that these are two different techniques. I think you have an incredible mastery of printmaking, especially this technique that is on wood and is known as reduction process. I know that Puerto Rico has a great tradition of printmaking. The Printmaking Biennial is one of the most important in Latin America, but you told me that you had learned it here in the United States. Tell us about it.

MARTA Well, I knew the importance of printmaking in Puerto Rico since college. But I always say that I am from Arecibo, I am a bit of a jibarita [country girl], and the truth is that I did not go to San Juan often. So, it is not that I knew a whole lot, but I knew that I had to make art, that I had something to say. But I wasn’t very good at writing, so I was looking for a way to express my thoughts and what I wanted to reflect on. When I started the master’s program (MFA at Temple University), I met a guy who made woodcuts. He made them differently, though. He would paint on paper first and then he would carve the wood, and finally, he would print on the painted paper. I loved it because I had done lithography and intaglio, but the wood itself…, the matrix…, what it meant to use these gouges, to break and remove the material, that fascinated me. So, he told me, “look, Marta, I can’t teach you. What you should do is to buy yourself a piece of wood, grab some gouges, draw a picture and start cutting.” And I went and did just that. But I was never one to make exact sketches because I am very hyperactive, and it seems to me that if I do something very exact and I start thinking about all the colors I will never finish it. So, I grabbed some markers to get an idea of where the lines were going to be and so I started to cut. What I love most about it is that it is super physical. Working in woodcut has a violence to it. You use gouges and blades, and you start removing and destroying. Especially with the reduction process, you destroy in order to create something out of this destruction. I also happen to be very much into colors. I use flat colors, but I like to combine, and from there I got different shades. All this happens very spontaneously. I start and don’t know where it is going to end. I like this because as I print a color, a red, and then add a blue, a different image emerges each time. I work with the errors, and it is a conversation with this matrix. A conversation between me, the wood, and the paper. That aggressiveness, that violence, and the creation of something from these three entities seems wonderful to me, and that’s why I keep doing it. The woodcut and the reduction process help me. Things happen in the moment and each piece is unique. I don’t make editions. I am not interested in making editions. For me, each one is unique. The process is so long that I do not like to extend it. Once I am done with one I want to move on to a new one and see something new appear every day.

“Especially with the reduction process you destroy in order to create something out of this destruction.”

JUAN CARLOS I would like to take this opportunity to enter the conversation because I have been one of Marta’s closest interlocutors for a long time. In fact, we are linked through our families, we are second or third cousins, and I was a friend of her sister Marvette. I have followed her work very closely and have written about it, with the intention of counteracting or interrupting readings that relate it to magical realism, the baroque, and all those common places. I relate to Marta’s work as a spectator, not as an expert in anything, but as someone who looks and relates to the images that she puts there. She was talking about that painting by Doña Myrna from 1991, and it is good to mention that Doña Myrna is the most important landscape painter of the twentieth century in Puerto Rico. We talked about that piece The Red Plantains and Marta’s gaze perhaps anthropomorphizes something when looking at that painting. I still see silence, but a lot of intensity too. They are infrared plantains. It is a horizon in latency. It has that hazy, opaque quality. The profiles of the people are never very noticeable when they appear in the landscapes of Myrna Báez. But I wanted, by way of introducing my comments about this work, to reflect on the anecdote that Martita tells— and I think she should collect Myrna’s suggestions or comments about her work—. But I really like this one about how in one of her pieces there are many. It is an observation about Martita’s ability to saturate space. Marta seems to be an artist of intensity and saturation, and I am not saying this in any pejorative way. In this sense, it seems important to me that she emphasizes that moment of her gaze on The Red Plantains through her own work as she is going through a process of mourning, of pain. That sets the scene a bit and the context to think about the subject of her work, and about the immortality of the crab.

PATRICIA Thank you Juan Carlos for summarizing and synthesizing in such a beautiful way the experiences that traverse this work as both an interlocutor of Marta and a spectator of her work. Thinking about intensity, I see how it manifests in her particular use of color, in the fact that she does not produce editions, and in the physical work, which has a connection with other female artists such as Zilia Sánchez, who have insisted on manual labor—not only with the hands but with the body—, and who have resisted industrial processes. In this sense, I think Marta is a bit of a sculptor.

MARTA It is interesting because I never saw myself like this and talking to you Patricia, that you see this work as having a relationship perhaps with a mural I can see how that can show in other pieces. I have actually just started to work on a mural, and it scares me. But I see what you mean, because now that I am making paper for the first time, what emerges from that process are sculptures. I am very excited because it is as if my characters are coming out and taking on a life of their own.

Mythology and Grief

PATRICIA We could now return to the themes that traverse this work. Juan Carlos pointed out how Marta’s own experience of mourning and pain informed this piece but… Where does this imagery that exists around the figure of the crab and immortality come from?

JUAN CARLOS Well, to answer this we could start by asking Marta… How did you get to the title? Not why? But how do you get there and decide on that title?

MARTA Let’s see if I can explain it … This work is about grief because I was thinking about the death of my sister which was extremely painful for me. I spent a year feeling lost; a tremendous loneliness, even though I had many dear friends and family around me, that’s a moment when one is on a quest to find out “why?”. They called me to create this piece that I knew would represent grief. By that time, Doña Myrna’s health had started to deteriorate and I felt like she was fading away little by little. I could hear it in her voice during our conversations. She was not just my mentor, she was also like my second mother. As I was looking for a title, I was thinking about how death often refuses to take you away. There are moments so difficult, and you think about death and you almost lose the sense of why you are here in this universe. That moment of mourning brought back memories of visits to my grandparent’s house when I was a child. The wonderful thing about being there was the silence. We would often stroll in silence. This was in stark contrast to my parent’s house full of all my siblings. I remember that during those walks we would see many crabs on the beach of Arecibo. That’s where the image of the crabs came from.

JUAN CARLOS Did you always call them “cangrejos” (crabs) Marta?

MARTA I’ve always said “cangrejos” (crabs), not juey [local Spanish word for crab]. And I remember these crabs running down the street and we would start chasing them. And if you look at the bottom of the piece, near the banana leaves, you can see these shells grouped together, like a crab graveyard. All these things are happening in 2013, the death of my sister, and I was writing the proposal for the project on gender violence. It was something me and my sister were working on together. She was going to be part of that project. Many things happen between 2013 and 2014. I am entering this whole universe around gender violence. That is why the centerpiece is a body with a gun. It is like a gun that is killing me, or that I am holding, or that is just floating around. I always thought of immortality as this death resisting to take you. You are right at that point, but you just cannot go beyond.

JUAN CARLOS But why choose this phrase as a title?

MARTA Immortality has to do with people’s fear of dying. It speaks of immortality because I am so empty, so lonely at this moment, and that is why I talk about the death that resists taking you. I remember a story from Greek mythology where the crab is talking to a god and he says that he never dies because he walks sideways and can dodge, and he never gets old. It might also be because my zodiac sign is cancer. These are all things that have to do with me, with what happens to me, and with who I am.

PATRICIA Someone from the audience comments that the title is also a saying.

JUAN CARLOS Yes, to say “I am thinking of the immortality of the crab” is to think of anything, to be suspended in your own thoughts, to daydream, wandering, thinking about “pregnant birds” is another way to say it, thinking about things that do not have much importance.

MARTA It also refers to a distracted person, someone who is not in the moment. And that was also how I felt. In the middle of this mourning, where I am, and I am not.

JUAN CARLOS Well, the phrase comes from that conversation that Zeus has with the crab. Zeus tells the crab that he can beat death because he can beat time. Time advances linearly, and the crab does not simply walk backward, but it moves in zigzag or in any direction. That is one of the mythological origins of the phrase, but there are others. There is a famous battle of Heracles, an illegitimate son of Zeus. Zeus liked women, not goddesses, mortals, not immortals. Heracles in one of his battles has to face the Hydra, a monster with many heads. Hera, who is Zeus’s wife and who obviously hates and feels powerful jealousy towards Heracles, summons Carcinos, a giant crab that lives on the shores of the Lerna lake. And that crab emerges and paralyzes Heracles, catches him with the levers but Heracles crushes him. At that moment Hera raises him to heaven and grants him the constellation. But I believe that the immortality of the crab— at least from my own fascination with the crab, whenever I see an image of the crab I am absorbed— for me it is also a personal story, always an intimate story.

JUAN CARLOS The discovery of the crab is always the discovery of the coastline, the coastal world, and it is also a delicacy. One of the first things my father did when we moved to a middle-class urbanization in Puerto Rico was build a jueyera [a corral for land crabs to clean and feed them) because my mother adored the juey, capturing them, feeding them, eating them. All of this is part of the process, and I remember many walks in solitude through the Luquillo mangrove. These are very formative scenes for me, very important when the children walked alone through the mangroves. And I remember the emergence of the juey, and every time I see them it seems to me that I am in another time. This is a creature that definitely comes from another time and another space. There are also other stories that come from Afro-Caribbean, Yoruba mythology. There are several patakíes, which are poetic stories that the babalawo mobilizes, he is the priest of divination in Ifá. There is one that I really like and is when Olofin or Obatalá creates the heads of human beings. The crab goes on to share the news all over the world and when the moment arrives to get his it is already too late, they have already been distributed. It seems to be a punishment. And the other one that is very interesting is that Orula, the god of divination who is always fighting and in revolutions, hides in the sea. The octopus throws ink to protect him. But when he comes out of the sea, he cannot find his board, which is what he uses for divination. The crab comes out of a cave with it and gives it back to him, and Orula promises that his children will never eat octopus or crab.

“The discovery of the crab is always the discovery of the litoral, the coastal world, and it is also a delicacy.”

MARTA Juan Carlos, you have used the crab a lot in your poetry, haven’t you?

JUAN CARLOS Yes, and I still use it. It is like a spell.

PATRICIA And the crab also appear in the diaries of Colón. I know this from Juan Carlos, who gave me to read those passages where the admiral narrates what he sees, or what he imagines when he has yet to find land.

JUAN CARLOS That is the crab’s first appearance in the archive of the Americas. That passage appears in his lost diary-travel log. They are in despair because they have not found land yet, and Colón is lying all the way because he realizes that he has traveled more nautical miles than he was supposed to. Well, he starts looking at the sea, but again it is also the beginning of that gaze towards the sea in which the subject is not looking at the sea but looking for land. He is looking out at the sea to see if there are pieces of wood (logs, branches, grass) indicating that the shore is close. He finds a piece of wood and on it is a crab, which surely must have been eaten because they were all starving.

PATRICIA I also see references in Marta’s work to the place of origin and to fertility. If you look at the lower left side there is something like an egg or a circular cavity, and from there comes a scattering of small crabs. This makes me think about the meaning of cancer in astrology, which rules the fourth house, that of the family, the home, and the mother.

JUAN CARLOS Yes, the crab is a lunar creature.

MARTA It is also a fighting creature. He is always alone and is small, but he is feisty. He gives a fight.

JUAN CARLOS Sometimes they are not so small.

MARTA I mean in proportion to the humans who are the ones attacking them the most.

JUAN CARLOS The crab has also been the subject of poems. The Mexican poet who was a member of our department, José Emilio Pacheco, has some extraordinary poems about the crab. But unlike the crab in the picture that appears as a herd, crabs do not do this except when they are going to mate, or when they are going to copulate. Late in the spring the females go out to look for a mate, and they emit pheromones, and that makes the males come out. This is how these migrations occur, which are massive. I remember in Vega Baja seeing little streets behind the reed bed all covered.

MARTA But this is not seen as much anymore.

JUAN CARLOS Now they are protected, but they were on the verge of disappearing. They have made a kind of come back. In Puerto Rico they protect them. There is a ban. But what you see as a cemetery, in your work I mean, it also refers to that time when they change their shell, and it is a very interesting ritual. Crab caves can be as long as six feet deep. When they are ready to shed their shell, they make this chamber that contains water. They sit there to drop the shell. It is a creature that is between two worlds, between the aquatic and the earthly. They are not diurnal nor they like herds. They are not tamable. You will never see them in a circus.

PATRICIA They also have the characteristic of being hard on the outside but very soft on the inside.

JUAN CARLOS Sure, they have the skeleton on the outside.

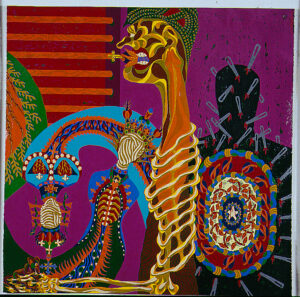

PATRICIA This is an interesting observation because I see in Marta’s work many references to bones, rather the skeleton-body. In your works, the bones are almost always the body itself. If I remember correctly, there were references to bones or teeth in the installation that resulted from the work you did on the issue of gender violence. Could you tell us about this work?

Body and Resistance

MARTA Sure, that installation came about after I realized that the issue of gender violence being central to my work and that it affected a community. I wanted to give voice to that community of women who experienced that violence. I was listening to stories that impacted my work, and I was wondering if I could do an installation or something that would allow me to connect with these women and their experiences through workshops. I wanted to see if it was possible to give these women a space to verbalize their stories. That is how this piece If I catch you: Body, Woman, Rupture emerges. It was installed here in DC but also in Puerto Rico. I originally meant for it to take place in Puerto Rico. I won a public arts grant in DC at that time, and I managed to do the installation in DC before taking it to Puerto Rico, with the great support of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Puerto Rico and its wonderful director Marianne Ramírez Aponte. I worked with around two hundred and twenty women. I decided to focus on the symbol of what keeps us together, what enables us to be upright and to be a standing being: the spinal bone—not just any bone like I had represented before. I wanted to explore what these women had in common, what connected them to each other, So I asked them what the spinal cord meant to them. And they would stand firm and say “it means strength, and that’s what holds us together.” Bones in my work have not only to do with death. They are also like shells or shields. Sometimes these bones are around the skin, or sometimes they are exposed, as something that protects us.

“Bones in my work have not only to do with death. They are also like shells or shields. Sometimes these bones are around the skin, or sometimes they are exposed, as something that protects us.”

JUAN CARLOS There are two things I want to say, the audience wants to contribute something. Eyda Merediz says that in Cuba they say “the immortality of the Moorish crab” and Dorothy Bell Ferrer says that she has seen them in Puerto Nuevo and Vega Baja. I also have friends who say that in some places they are back in numbers. I think the crab’s exoskeleton is its paradox.

MARTA Yes, when I think of “The Immortality of the Crab” and about the lying figure in Doña Myrna’s work “The Red Plantains”, and I see a figure on the horizon that is a body with a skeleton around it. The crab has this external skeleton.

JUAN CARLOS But I still like the resonance of the phrase, that more than a concern with death, with immortality, it is a figuration of the eternity of the moment. Somehow whoever is absorbed in thinking about the immortality of the crab is surrendered to this now, he or she is outside of time. That is the eternity of these animals and their beauty. They occupy the now outside of this linear conception of past, present, and future. The full now is the now of the image, of contemplation. It is being distracted, suspended in your own thought. It is an extraordinary experience, very comforting. You are not in the order of production, you are not complying or owing anything. You are enjoying the images. This is not like the emphasis on violence, breakage, and misogyny in Puerto Rico, but it is, in a way, that recurrence, that the juey always reappears. More than resistance it is this kind of eternity of something that never leaves the scene. And that does not get along with the light. The light imprisons them. The light literally blinds them. It paralyzes them.

MARTA And they have an incredible ability to regenerate themselves. They lose a limb and they can just grow it back.

JUAN CARLOS Yes, there is even a phrase that says—speaking of its strength and resistance—that “the juey is a shell even in the eyes.” And an annoying person is “a juey’s shell”. Just imagine, if you are eating rice with juey and suddenly there is a little shell, it is very unpleasant.

PATRICIA Thinking about what Juan Carlos said about the moment and the now, I see another connection with the way in which Marta works with space, from a cosmological concept. She suggests a simultaneity of times through these crossroads as if there were events unfolding at the same time. We see it in The Immortality of the Crab with the panels, but also in the installation where you reorganize the space through a geometric system, like coordinates. I wanted to return to this topic because Jossianna Arroyo from the audience comments that she was able to see the installation in Puerto Rico and that she would like to know about the assembly and that process in relation to the different spaces.

MARTA This is very interesting because when I conceived the project, I thought to create it in Puerto Rico. It was going to be at the Museum of Contemporary Art. But that didn’t happen. Then Marvette dies and I disappear from the art scene for several years. Then I get back to it. I win the grant and am able to make it happen in DC. I always thought it should be exhibited in a public space so that people come and have a relationship with what is happening and perhaps they can reflect on it. It had to be a public space. It was not easy to find one in Washington, D.C. I saw this space at the Reeves Municipal Building in central DC (14th & U st NW) that was very open, with a lot of natural light, and there were government offices where many people from different social classes would go. I liked that because that was my vision for the piece: that many different people would see it. I made the exhibition happen. I had been working on this installation for a year, thinking about it, securing all the permits. I go to an organization that works with women survivors of gender violence. I do research and take classes to learn how to approach the issue and these women. It was also a very complex installation, with an intricate floor design and various spatial arrangements. This was meant for people to have to look down, where these silhouettes laid down like dead bodies. I wanted the viewers to reflect about their position on the issue and what they were doing about it. There were also words from a Puerto Rican poet Vanessa Droz, as a companion poem to this piece.

MARTA What happened in D.C. is that a person in the public saw the dolls made by the women during the workshops, and on which we had worked for many months and mistakenly thought the dolls represented her, not the women the survivors who had made them. The dolls were supported by the spine because that is what I think would give the idea of feeling strong and that was something they had in common. The women had even made the faces, chosen clothes, and thought about colors. The dolls were a reflection of themselves and the expression of their thoughts about their own bodies and their own wounds. We discussed using the pantyhose as the material to make these dolls. It is a fabric that breaks easily just like the skin, and that has the appearance of sutures and wounds during the healing process. What happened in the United States as opposed to Puerto Rico, is that they saw the exhibition as if I had hanged these dolls. And a huge problem arose. The city wanted to deinstall the piece because a woman said that those dolls were hanged/lynched. And I tell them no, that they are supported, held by the armpits. I tell them that these dolls were made mostly by immigrant Latin American women. And the fight was so big that I was going every day for a whole month to the exhibition center expecting the installation to be forcefully removed from that space. Legal letters had to be sent for them to stop. It was truly censorship. It is terrible that they did not give importance to the work and the stories of these women.

MARTA In Puerto Rico it was completely different with Marianne Ramírez Aponte, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, and the wonderful organization Peace for Women. I wanted to reach not only the metropolitan area but the interior of the island, Arecibo, the mountains, etc. We worked with young people in juvenile institutions and the Correctional Department, as well as with a group of immigrant women from the Dominican Republic and many other organizations. And it is incredible that while making the dolls these women felt heard and accompanied. For the first time, they were able to verbalize and share their stories. That was the difference. In Puerto Rico, there was a complete accompaniment. The work itself created a space to speak and reflect on these issues. But in D.C. there was incredible censorship. I think it is because people here do not really want to talk about what gender violence is in these communities, or that they don’t want to see the representation of a naked “body” even though that is how the women represented themselves.

PATRICIA I think that maybe there is an expectation about what a work on that subject should be, especially in the context of public art. People expect something more sanitized. Seeing something like that so confrontational is uncomfortable.

JUAN CARLOS Looking at Marta’s pieces is never comforting, much of their strength comes from that. These works are uncomfortable and disturbing. The animals always have open mouths, open genitals. But it is not a vulva or a mouth in a process of joy or eroticism, it is in fact linked to situations of violence. Marta has been very elegant because she has a huge heart. But what Marta experienced was censorship from an office that responds to the mayor of Washington D.C., and a person who saw an installation declared that Marta’s installation played with the idea of lynching. And once this person saw and said this, was not able to see anything else. Then dealing with that office and its utter lack of sophistication, of artistic and political culture, was quite frustrating and generated a lot of anger. What they wanted was for her to dismantle it, but she sought advice and decided not to because if they dismantled it, it was openly censorship and there was reason to generate some kind of lawsuit. I believe that we live in a moment in which moralism coming from all sectors is eating up any proposal of openness or thought. It is very sad. It is a kind of new obscurantism where there are issues that cannot be touched or thought about.

JUAN CARLOS I also wanted to say that a little while ago Dorothy Bell Ferrer from the audience commented that jueyes is a more or less popular nickname in eastern Puerto Rico, in Loíza, Carolina, Fajardo, coastal towns, Afro-Puerto Rican towns, black towns. The juey has been a recurrence. That is the eternity of these animals. Its immortality is that it has provided food and sustenance to marginalized communities. In some archaeological sites in Puerto Rico, trays full of juey shells have been found, which means that they provided protein and sustenance. Puerto Ricans love to eat juey. I’ve been to other islands and they say no, why eat that? I believe that this relationship of pleasure and suffering, of imagination, of pain and despair, is something that the crab magnetizes.

PATRICIA That is why when I saw this work with women, I thought about the importance of Marta not calling them victims but survivors of gender violence. I don’t like the word victim. Thinking and speaking from a place of strength returns the stories back to them. Beyond a narrative of good and evil, it implicates considering the personal stories, that of the individual who lives it.

MARTA It gives them a powerful voice because they don’t have a space.

PATRICIA Yes, of course, it is not that they do not have a voice, what is given is a space of listening.

JUAN CARLOS And we must not lose sight of the potential of the image in all this, both for those who reject it and for those who want to explore it. We come into contact with something, we touch something, it is a very specific sensory experience, and different reactions arise when it comes to this subject, even the worst ones.

MARTA Of course, this was something I said to those who questioned the piece. Gender violence is not pretty. You have to see what it is, and this was an opportunity to reflect on that. There were many dolls that were naked, and it seemed wonderful to see them like this because the body is a weapon, it is a shield, that is, this is me and this is my body, but it is not pretty. A personal story is what it is.

JUAN CARLOS There is a pedagogical conception of the image and even an educational one. As if by seeing something we are going to be better citizens and better people. But it is actually an exposure to the thought and experience of the other.

MARTA Also, pain comes from different stories. And this is a way of sharing the different stories of violence. It’s sad because it doesn’t allow a dialogue between different cultures and experiences.

PATRICIA I want to thank you both wholeheartedly for accepting this invitation. It was a pleasant, provocative, and above all very enriching conversation. Marta, I have one last question for you. Is there a project that you have in mind and that you would like to carry out? Maybe something very ambitious, or a large-scale installation?

MARTA First I want to thank you dear Patricia for having invited me to this conversation and for being part of this wonderful project. To Kim for her commitment to making the stories and works of women known, and to my dear cousin Juan Carlos for always being present. I always think that it would be wonderful to be able to take the installation “I”m Gonna Get You… Body Woman, Rupture” to other communities. We must return to the conversation about gender violence and reflect on whether we are doing enough as a community regarding this issue. I am also creating new works on paper. Torsos and bodies of women that are more sculptural. I would like to work on this project with other women with their perspectives. This reflection on the female body and the issue of gender violence continues to be central to my work. I think our survival stories are written on our bodies.

❧

This is an edited transcript of a Zoom conversation that took place on March 26, 2021, at 5 p.m. ET between Marta Pérez García, Juan Carlos Quintero Herencia, and Patricia Ortega-Miranda.

This project is supported in part by The University of Maryland Art Gallery

Thanks to Marta Pérez García, Juan Carlos Quintero Herencia, Patricia Ortega-Miranda, and Kim Schoenstadt for the interview, additions, and editing.